Lyme, Depression, and Suicide

March 1, 2014 in Science/Research by Dr. Robert C. Bransfield, MD

In the late 1970s, I treated a depressed patient who appeared to have more than just depression. Her weight increased from 120 to 360 pounds, she was suicidal, had papilledema, arthritis, cognitive impairments, and anxiety. This patient became disabled, went bankrupt, and had marital problems. Like many whose symptoms could not be explained, she was referred to a psychiatrist. However, I was never comfortable labeling her condition as just another depression.

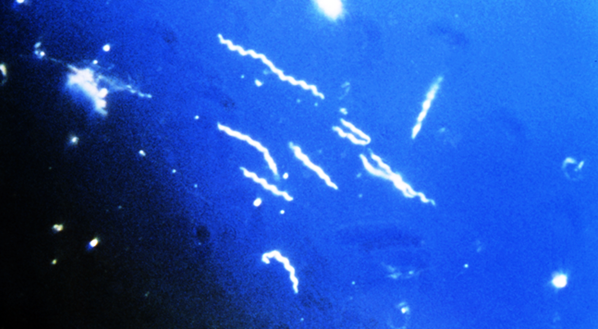

At the time, I did not consider her illness could be connected to other diagnostic entities such as neuroborreliosis, erythema migrans disease, erythema chronicum migrans, Bannwoth’s syndrome, Garin-Bujadoux syndrome, Montauk knee, or an arthritis outbreak in Connecticut. With time, the connection between Borrelia burgdorferi infections and mental illnesses such as depression became increasingly apparent.

In my database, depression is the most common psychiatric syndrome associated with late stage Lyme disease. Although depression is common in any chronic illness, it is more prevalent with Lyme patients than in most other chronic illnesses. There appears to be multiple causes, including a number of psychological and physical factors.

From a psychological standpoint, many Lyme patients are psychologically overwhelmed by the large multitude of symptoms associated with this disease. Most medical conditions primarily affect only one part of the body, or only one organ system. As a result, patients singularly afflicted can do activities which allow them to take a vacation from their disease. In contrast, multi-system diseases such as chronic Lyme disease can penetrate into multiple aspects of a person’s life. It is difficult to escape for periodic recovery. In many cases, this results in a vicious cycle of disappointment, grief, chronic stress, and demoralization.

It should be noted that depression is not only caused by psychological factors. Physical dysfunction can directly cause depression. Endocrine disorders such as hypothyroidism, which cause depression, are sometimes associated with Lyme disease and further strengthen the link between Lyme disease and depression.

The most complex link is the association between Lyme disease and central nervous system functioning. Lyme encephalopathy results in the dysfunction of a number of different mental functions. This in turn results in cognitive, emotional, vegetative, and/or neurological pathology. Although all Lyme disease patients demonstrate many similar symptoms, no two patients present with the exact same symptom profile.

Other mental syndromes associated with late state Lyme disease, such as attention deficit disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, etc., may also contribute to the development of depression. Dysfunction of other specific pathways may more directly cause depression. The link between encephalopathy and depression has been more thoroughly studied in other illnesses, such as stroke.

The neura1 injury from a stroke causes neural dysfunction that causes depression. Injury to specific brain regions has different statistical correlation with the development of depression. Once depression or other psychiatric syndromes occur with Lyme disease, treating them effectively improves other Lyme disease symptoms as well and prevents the development of more severe consequences, such as suicide.

Suicidal tendencies are common in neuropsychiatric Lyme patients. There have been a number of completed suicides in Lyme disease patients and one published account of a combined homicide/suicide. Suicide accounts for a significant number of the fatalities associated with Lyme disease. In my database, suicidal tendencies occur in approximately 1/3 of Lyme encephalopathy patients. Homicidal tendencies are less common, and occurred in about 15% of these patients. Most of the Lyme patients displaying homicidal tendencies also showed suicidal tendencies. In contrast, the incident of suicidal tendencies is comparatively lower in individuals suffering from other chronic illnesses such as cancer, cardiac disease, and diabetes.

To better understand the link between Lyme disease and suicide, let’s first look at an overview of suicide. Chronic suicide risk is particularly associated with an inability to appreciate the pleasure of life (anhedonia). People tolerate pain without becoming suicidal, but an inability to appreciate the pleasure of life highly correlates with chronic suicidal risk. Of course, there are many other factors that also contribute to chronic risk. For example, one study demonstrated that 50% of patients with low levels of a serotonin metabolite (5HIAA) in the cerebrospinal fluid committed suicide within two years.

Apart from factors which contribute to chronic suicidal risk, there are also factors which trigger an actual attempt, i.e.; a recent loss, acute intoxication, unemployment, recent rejection, or failure. There is much impairment from Lyme disease which increases suicidal risk factors. However, suicidal tendencies associated with Lyme disease follow a somewhat different pattern than is seen in other suicidal patients.

In Lyme patients, suicide is difficult to predict. Attempts are sometimes associated with intrusive, aggressive, horrific images. Some attempts are very determined and serious. Although a few attempts may be planned in advance, most are of an impulsive nature. Both suicidal and homicidal tendencies can be part of a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction.

I cannot emphasize enough the behavioral significance of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. As part of this reaction, I have seen and heard numerous patients describe becoming suddenly aggressive without warning. I can appreciate skepticism regarding this statement. How can this be explained? Like many other symptoms seen in Lyme disease, it challenges our medical capabilities. In view of this observation, I advise that antibiotic doses be increased very gradually when suicidal or homicidal tendencies are part of the illness.

Although I have discussed the significance of depression and suicide associated with Lyme disease, I would like to emphasize that treatment does help. Combined treatment which addresses both the mental and somatic components of the illness significantly improves the overall prognosis. This is supported by clinical observation and laboratory research showing antidepressant treatment improves immunocompetence.

It has been demonstrated in vitro that antidepressants which act on the serotonin 1A receptor (most antidepressants) increase natural killer cell activity. In addition, there are undoubtedly other indirect effects on the immune system through other neural or neuroendocrine and autonomic pathways. To state this more concisely - antidepressants can result in antibiotic effects, and antibiotics can have antidepressant effects.

Most depression and suicidal tendencies often respond to treatment. Suicide is a permanent response to a temporary problem. Many people who survive very serious attempts go on to lead productive and gratifying lives. Suffering can be reduced. The joy of life can be restored. Needless death can be prevented. Don’t give up hope. There are answers, solutions, and assistance. There is life after Lyme.

At the time, I did not consider her illness could be connected to other diagnostic entities such as neuroborreliosis, erythema migrans disease, erythema chronicum migrans, Bannwoth’s syndrome, Garin-Bujadoux syndrome, Montauk knee, or an arthritis outbreak in Connecticut. With time, the connection between Borrelia burgdorferi infections and mental illnesses such as depression became increasingly apparent.

In my database, depression is the most common psychiatric syndrome associated with late stage Lyme disease. Although depression is common in any chronic illness, it is more prevalent with Lyme patients than in most other chronic illnesses. There appears to be multiple causes, including a number of psychological and physical factors.

From a psychological standpoint, many Lyme patients are psychologically overwhelmed by the large multitude of symptoms associated with this disease. Most medical conditions primarily affect only one part of the body, or only one organ system. As a result, patients singularly afflicted can do activities which allow them to take a vacation from their disease. In contrast, multi-system diseases such as chronic Lyme disease can penetrate into multiple aspects of a person’s life. It is difficult to escape for periodic recovery. In many cases, this results in a vicious cycle of disappointment, grief, chronic stress, and demoralization.

It should be noted that depression is not only caused by psychological factors. Physical dysfunction can directly cause depression. Endocrine disorders such as hypothyroidism, which cause depression, are sometimes associated with Lyme disease and further strengthen the link between Lyme disease and depression.

The most complex link is the association between Lyme disease and central nervous system functioning. Lyme encephalopathy results in the dysfunction of a number of different mental functions. This in turn results in cognitive, emotional, vegetative, and/or neurological pathology. Although all Lyme disease patients demonstrate many similar symptoms, no two patients present with the exact same symptom profile.

Other mental syndromes associated with late state Lyme disease, such as attention deficit disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, etc., may also contribute to the development of depression. Dysfunction of other specific pathways may more directly cause depression. The link between encephalopathy and depression has been more thoroughly studied in other illnesses, such as stroke.

The neura1 injury from a stroke causes neural dysfunction that causes depression. Injury to specific brain regions has different statistical correlation with the development of depression. Once depression or other psychiatric syndromes occur with Lyme disease, treating them effectively improves other Lyme disease symptoms as well and prevents the development of more severe consequences, such as suicide.

Suicidal tendencies are common in neuropsychiatric Lyme patients. There have been a number of completed suicides in Lyme disease patients and one published account of a combined homicide/suicide. Suicide accounts for a significant number of the fatalities associated with Lyme disease. In my database, suicidal tendencies occur in approximately 1/3 of Lyme encephalopathy patients. Homicidal tendencies are less common, and occurred in about 15% of these patients. Most of the Lyme patients displaying homicidal tendencies also showed suicidal tendencies. In contrast, the incident of suicidal tendencies is comparatively lower in individuals suffering from other chronic illnesses such as cancer, cardiac disease, and diabetes.

To better understand the link between Lyme disease and suicide, let’s first look at an overview of suicide. Chronic suicide risk is particularly associated with an inability to appreciate the pleasure of life (anhedonia). People tolerate pain without becoming suicidal, but an inability to appreciate the pleasure of life highly correlates with chronic suicidal risk. Of course, there are many other factors that also contribute to chronic risk. For example, one study demonstrated that 50% of patients with low levels of a serotonin metabolite (5HIAA) in the cerebrospinal fluid committed suicide within two years.

Apart from factors which contribute to chronic suicidal risk, there are also factors which trigger an actual attempt, i.e.; a recent loss, acute intoxication, unemployment, recent rejection, or failure. There is much impairment from Lyme disease which increases suicidal risk factors. However, suicidal tendencies associated with Lyme disease follow a somewhat different pattern than is seen in other suicidal patients.

In Lyme patients, suicide is difficult to predict. Attempts are sometimes associated with intrusive, aggressive, horrific images. Some attempts are very determined and serious. Although a few attempts may be planned in advance, most are of an impulsive nature. Both suicidal and homicidal tendencies can be part of a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction.

I cannot emphasize enough the behavioral significance of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. As part of this reaction, I have seen and heard numerous patients describe becoming suddenly aggressive without warning. I can appreciate skepticism regarding this statement. How can this be explained? Like many other symptoms seen in Lyme disease, it challenges our medical capabilities. In view of this observation, I advise that antibiotic doses be increased very gradually when suicidal or homicidal tendencies are part of the illness.

Although I have discussed the significance of depression and suicide associated with Lyme disease, I would like to emphasize that treatment does help. Combined treatment which addresses both the mental and somatic components of the illness significantly improves the overall prognosis. This is supported by clinical observation and laboratory research showing antidepressant treatment improves immunocompetence.

It has been demonstrated in vitro that antidepressants which act on the serotonin 1A receptor (most antidepressants) increase natural killer cell activity. In addition, there are undoubtedly other indirect effects on the immune system through other neural or neuroendocrine and autonomic pathways. To state this more concisely - antidepressants can result in antibiotic effects, and antibiotics can have antidepressant effects.

Most depression and suicidal tendencies often respond to treatment. Suicide is a permanent response to a temporary problem. Many people who survive very serious attempts go on to lead productive and gratifying lives. Suffering can be reduced. The joy of life can be restored. Needless death can be prevented. Don’t give up hope. There are answers, solutions, and assistance. There is life after Lyme.

About the author

Dr. Robert Bransfield, MD is a psychiatrist specializing in the link between mental health and microbes. You can learn more by visiting Dr. Robert Bransfield's website mentalhealthandillness.com.

latest posts

tags

Disclaimer: The information on this website is not a substitute for professional medical advice.

Always consult with your treating physician before altering any treatment protocol.

Always consult with your treating physician before altering any treatment protocol.