Herx Reaction Fundamentals

February 8, 2012 in Science/Research by Bryan Rosner | Comments

You get to see more and more of my book, "Lyme Disease and Rife Machines", online for free these days! This post is an excerpt from the book addressing herxheimer reactions, also known as “herx reactions.” Have no clue what that is? Keep reading to find out. Believe it or not, the herx reaction is one of the most important topics you will ever study as a Lyme disease patient or practitioner.

Understanding Lyme disease symptoms

The first step to understanding the recovery process is reviewing the herx reaction. To appreciate the herx reaction, it is necessary to first examine regular, ongoing Lyme disease symptoms.

Consider what happens when you get the flu: You get body aches, chills, fever, nausea, lack of appetite, fatigue, lethargy, and sometimes additional symptoms. What you may not know is that these flu symptoms are not caused simply by the presence of a flu infection in the body. Symptoms experienced are actually a result of your body’s immune system responding to the flu infection via inflammation.

These unpleasant symptoms of inflammation are essential to getting over the flu. Chills are your body’s way of telling you to bundle up and get warmer, and the actual shaking involved with the chills is your body’s way of increasing core body temperature through motion. After you've bundled up and had the chills for a while, a fever results and your body uses the fever to activate the immune system. A fever triggers a cascade of immune system activities necessary to fight infection. Lack of appetite is your body telling you that there isn't enough energy to process food – all available energy is fighting the infection.

Muscle aches, soreness and inflammation are the result of your immune system responding to the infection and your body fighting back. Without these symptoms present during the flu, your body would not be fighting and you would not get over the common flu.

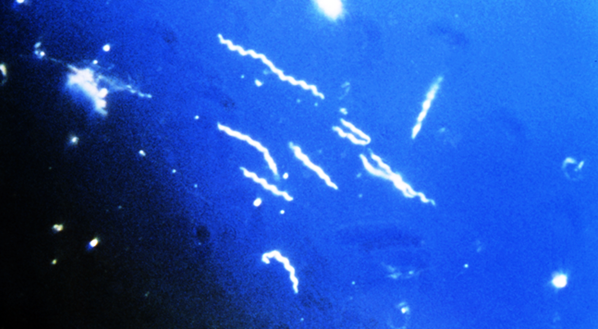

Because Lyme disease is an infection, as the flu is, most symptoms experienced by a Lyme disease sufferer are the body’s response to the infection. The spirochetes themselves (their physical presence in the body) are not responsible for the majority of symptoms in Lyme disease. As with the flu, symptoms of Lyme disease are an indication that the body is responding and fighting. Yet, curiously, even in some of the worst Lyme disease infections, symptoms can wax and wane, even with occasional symptom-free periods.

Some people report that when they were first infected with Lyme disease, they were plagued with flu-like symptoms and even bedridden for a while -- and then things seem to get better, and their symptoms became less intense. For example, many people with Lyme disease are still able to walk around, go to the movies, even work full or part time – all this while they have a raging, active infection which is much more dangerous than the flu.

Lyme disease sufferers often do not get fevers – sometimes are even incapable of getting a fever. Considering that a fever is the body’s most useful tool in fighting infection, this observation is also peculiar. The flu involves intense, continual symptoms. Lyme disease often does not. Lack of debilitating symptoms, absence of fevers, and presence of symptom-free periods may convince a person infected with Lyme disease that they aren’t really that sick. This is an understandable assumption because in most illnesses, lack of symptoms does indicate that you are on the mend.

The truth as it pertains to Lyme disease is shocking. Lack of expected symptoms indicates that the infection is actually winning – it is not gone! The body fighting is what causes symptoms. So, if there are no symptoms, there is no fight. The infection has free reign and the immune system is not doing its job.

Why does the human immune system fight the common flu but not Lyme disease? What separates Lyme disease from the flu is that the Lyme spirochete tricks the immune system into living in harmony with the infection. The immune system’s ability to identify Lyme disease as a foreign invader is jammed and disabled by the advanced infective activities of the bacteria. The infection acclimatizes to the immune system.

Lyme disease researchers have identified many specific strategies employed by the Lyme disease bacteria to accomplish this. One of the most creative involves the spirochete concealing the part of its bacterial body containing a protein code that tells your immune system it is an invader. Not only can it hide this code, it can change it quickly enough to stay ahead of the immune system recognition process. This phenomenon is called antigen-shifting. The flu virus cannot do this. Other methods of immune system evasion are beyond the scope of this book but can easily be found in other Lyme disease literature.

The result of the infection’s ability to evade the immune system is that the bacteria can proliferate and grow for years without challenge from the immune system. Enter chronic Lyme disease.

Although the bacteria are able to persist largely unchallenged, a person will still experience symptoms of disease. People with chronic Lyme disease, although often not as acutely ill as people with the flu, are very sick. In "stealth mode" the Lyme disease spirochete secretes a neurotoxin that is highly destructive to body functions and can result in stressed liver detoxification, lethargy and fatigue, muscle soreness, mental confusion, emotional instability, hypothalamus dysfunction, and much more.

Hypothalamus dysfunction eventually throws off the thyroid and adrenal glands and other hormonal functions, which results in a cascade of dozens of other symptoms. Additionally, because the spirochete’s evasion is not 100% successful, the immune system may sometimes "catch a glimpse" of the infection, resulting in symptoms of inflammation and immune system activation. A person can experience chills, headache, sore throat, nausea, fatigue, muscle aches, enlarged spleen, cold extremities, etc.

The most notable symptoms are typically in the brain. The brain can become inflamed, as it would with any other bacterial infection. Encephalopathy or meningitis may occur, along with very scary brain symptoms including confusion, "Lyme rage", depression, memory loss, etc.

Based on this information, we can establish that the two primary causes of symptoms in Lyme disease are neurotoxin circulation (which persists despite immune system acclimatization) and inflammation (which decreases as the infection acclimatizes to the immune system). Let’s see how this relates to herx reactions.

Understanding the herx reaction

Most Lyme disease sufferers know of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction as a "herx", or "getting worse before you get better", or a "healing crisis". The herx reaction is documented to take place in Syphilis, Lyme disease, and a few other spirochetal illnesses, all capable of evading the immune system. The reaction is named after two scientists who discovered the phenomenon. Adolf Jarisch (1850-1902), was an Austrian dermatologist who published his description of the reaction in 1895. Karl Herxheimer (1861-1944) was a German dermatologist who published his description of the reaction in 1902.

The definition of a herx reaction is an increase in the symptoms of a spirochetal disease (such as Syphilis, Lyme disease, or relapsing fever) occurring in some persons when treatment with spirocheticidal therapy is started. In the case of Lyme disease, the herx reaction is an increase in the symptoms caused by neurotoxin circulation and inflammation:

The combination of the above two events constitute a herx reaction. After anti-Lyme therapy is stopped and time passes, the herx reaction slowly ends. The bacteria that were unaffected by treatment remain in the body, largely undetected. These bacteria were not affected because they did not happen to be in the spirochete portion of their life cycle when the treatment took place.

The stalemate between Lyme disease and the immune system will continue after a herx reaction. Only now, some progress has been made. The treatment, in combination with a temporarily activated immune system, has killed some bacteria. Bacterial load was reduced, and consequently the person will experience a decrease in ongoing symptoms of inflammation and neurotoxin circulation. The decrease in symptoms may be subtle because only a small percentage of the bacterial load was effected.

Understanding Lyme disease symptoms

The first step to understanding the recovery process is reviewing the herx reaction. To appreciate the herx reaction, it is necessary to first examine regular, ongoing Lyme disease symptoms.

Consider what happens when you get the flu: You get body aches, chills, fever, nausea, lack of appetite, fatigue, lethargy, and sometimes additional symptoms. What you may not know is that these flu symptoms are not caused simply by the presence of a flu infection in the body. Symptoms experienced are actually a result of your body’s immune system responding to the flu infection via inflammation.

These unpleasant symptoms of inflammation are essential to getting over the flu. Chills are your body’s way of telling you to bundle up and get warmer, and the actual shaking involved with the chills is your body’s way of increasing core body temperature through motion. After you've bundled up and had the chills for a while, a fever results and your body uses the fever to activate the immune system. A fever triggers a cascade of immune system activities necessary to fight infection. Lack of appetite is your body telling you that there isn't enough energy to process food – all available energy is fighting the infection.

Muscle aches, soreness and inflammation are the result of your immune system responding to the infection and your body fighting back. Without these symptoms present during the flu, your body would not be fighting and you would not get over the common flu.

Because Lyme disease is an infection, as the flu is, most symptoms experienced by a Lyme disease sufferer are the body’s response to the infection. The spirochetes themselves (their physical presence in the body) are not responsible for the majority of symptoms in Lyme disease. As with the flu, symptoms of Lyme disease are an indication that the body is responding and fighting. Yet, curiously, even in some of the worst Lyme disease infections, symptoms can wax and wane, even with occasional symptom-free periods.

Some people report that when they were first infected with Lyme disease, they were plagued with flu-like symptoms and even bedridden for a while -- and then things seem to get better, and their symptoms became less intense. For example, many people with Lyme disease are still able to walk around, go to the movies, even work full or part time – all this while they have a raging, active infection which is much more dangerous than the flu.

Lyme disease sufferers often do not get fevers – sometimes are even incapable of getting a fever. Considering that a fever is the body’s most useful tool in fighting infection, this observation is also peculiar. The flu involves intense, continual symptoms. Lyme disease often does not. Lack of debilitating symptoms, absence of fevers, and presence of symptom-free periods may convince a person infected with Lyme disease that they aren’t really that sick. This is an understandable assumption because in most illnesses, lack of symptoms does indicate that you are on the mend.

The truth as it pertains to Lyme disease is shocking. Lack of expected symptoms indicates that the infection is actually winning – it is not gone! The body fighting is what causes symptoms. So, if there are no symptoms, there is no fight. The infection has free reign and the immune system is not doing its job.

Why does the human immune system fight the common flu but not Lyme disease? What separates Lyme disease from the flu is that the Lyme spirochete tricks the immune system into living in harmony with the infection. The immune system’s ability to identify Lyme disease as a foreign invader is jammed and disabled by the advanced infective activities of the bacteria. The infection acclimatizes to the immune system.

Lyme disease researchers have identified many specific strategies employed by the Lyme disease bacteria to accomplish this. One of the most creative involves the spirochete concealing the part of its bacterial body containing a protein code that tells your immune system it is an invader. Not only can it hide this code, it can change it quickly enough to stay ahead of the immune system recognition process. This phenomenon is called antigen-shifting. The flu virus cannot do this. Other methods of immune system evasion are beyond the scope of this book but can easily be found in other Lyme disease literature.

The result of the infection’s ability to evade the immune system is that the bacteria can proliferate and grow for years without challenge from the immune system. Enter chronic Lyme disease.

Although the bacteria are able to persist largely unchallenged, a person will still experience symptoms of disease. People with chronic Lyme disease, although often not as acutely ill as people with the flu, are very sick. In "stealth mode" the Lyme disease spirochete secretes a neurotoxin that is highly destructive to body functions and can result in stressed liver detoxification, lethargy and fatigue, muscle soreness, mental confusion, emotional instability, hypothalamus dysfunction, and much more.

Hypothalamus dysfunction eventually throws off the thyroid and adrenal glands and other hormonal functions, which results in a cascade of dozens of other symptoms. Additionally, because the spirochete’s evasion is not 100% successful, the immune system may sometimes "catch a glimpse" of the infection, resulting in symptoms of inflammation and immune system activation. A person can experience chills, headache, sore throat, nausea, fatigue, muscle aches, enlarged spleen, cold extremities, etc.

The most notable symptoms are typically in the brain. The brain can become inflamed, as it would with any other bacterial infection. Encephalopathy or meningitis may occur, along with very scary brain symptoms including confusion, "Lyme rage", depression, memory loss, etc.

Based on this information, we can establish that the two primary causes of symptoms in Lyme disease are neurotoxin circulation (which persists despite immune system acclimatization) and inflammation (which decreases as the infection acclimatizes to the immune system). Let’s see how this relates to herx reactions.

Understanding the herx reaction

Most Lyme disease sufferers know of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction as a "herx", or "getting worse before you get better", or a "healing crisis". The herx reaction is documented to take place in Syphilis, Lyme disease, and a few other spirochetal illnesses, all capable of evading the immune system. The reaction is named after two scientists who discovered the phenomenon. Adolf Jarisch (1850-1902), was an Austrian dermatologist who published his description of the reaction in 1895. Karl Herxheimer (1861-1944) was a German dermatologist who published his description of the reaction in 1902.

The definition of a herx reaction is an increase in the symptoms of a spirochetal disease (such as Syphilis, Lyme disease, or relapsing fever) occurring in some persons when treatment with spirocheticidal therapy is started. In the case of Lyme disease, the herx reaction is an increase in the symptoms caused by neurotoxin circulation and inflammation:

- Increased neurotoxin circulation - As you’ve seen, during normal life cycle activities, the spirochete secretes neurotoxins. However, when the spirochete is killed, an intense release of neurotoxins from dying bacterial organisms floods the body. Increased neurotoxin circulation can last from a few hours to a few weeks, depending on the sufficiency of a person’s detoxification pathways, as well as the extent of the kill-off.

- Increased inflammation - Whether using rife machines or antibiotics (or some other anti-Lyme activity), spirochetes will become irritated or killed during the attack. Their delicate, once-hidden antigens (protein codes which alert the immune system to the presence of an invader) will be exposed as spirochetes die and their bacterial proteins enter circulation. Suddenly the immune system will detect multitudes of spirochetes infecting various locations of the body. The immune system was unable to "see" the spirochetes before the kill off, but when the infection does become visible, major immune system activation begins. The body starts fighting during a herx reaction. So symptoms of inflammation increase as they would in the flu. The reaction can vary from person to person, depending on the extent of the infection, location of infected areas, and body constitution. Although the inflammatory portion of the herx response is unpleasant and involves greatly increased symptoms, it is a sign that therapy was successful because spirochetes are dying and the immune system is fighting. Lyme disease cannot be eradicated if the immune system is not activated.

The combination of the above two events constitute a herx reaction. After anti-Lyme therapy is stopped and time passes, the herx reaction slowly ends. The bacteria that were unaffected by treatment remain in the body, largely undetected. These bacteria were not affected because they did not happen to be in the spirochete portion of their life cycle when the treatment took place.

The stalemate between Lyme disease and the immune system will continue after a herx reaction. Only now, some progress has been made. The treatment, in combination with a temporarily activated immune system, has killed some bacteria. Bacterial load was reduced, and consequently the person will experience a decrease in ongoing symptoms of inflammation and neurotoxin circulation. The decrease in symptoms may be subtle because only a small percentage of the bacterial load was effected.

About the author

Bryan Rosner is the author of 4 books on Lyme disease treatment. His latest book, "Freedom From Lyme Disease", was published in August, 2014. Bryan lives in Northern California with his wife and three children.

latest posts

tags

Disclaimer: The information on this website is not a substitute for professional medical advice.

Always consult with your treating physician before altering any treatment protocol.

Always consult with your treating physician before altering any treatment protocol.