Interview: Dr. Joseph Jemsek, MD, The Power Of Truth

May 25, 2014 in Interviews by Tina J. Garcia, with Dr. Joseph Jemsek, MD

Cognitive dysfunction. Excruciating pain. Crushing fatigue. These are the daily aches and pains of suffering Lyme disease patients. Medical board prosecutions and costly lawsuits. These are the daily aches and pains of Lyme medical practitioners who honor the medical profession by serving those infected with Borrelia and other vector-borne disease. These are the soldiers who have been forcefully thrust into this saga called the Lyme Wars.

The Lyme disease community is an army with limited resources, limited strength and the limited ability to have our voices heard amid the roar of the mighty Giant. We are like young David from days of old-facing formidable foes which show no mercy or compassion for our plight, but only disdain and contempt for our resilient survival. We are painfully experiencing the dominance of government agencies, the wealthy insurance industry and influential medical societies, all of which wield power capable of crushing anything and anyone who stands in the path of their objectives.

In defending our position, the Lyme community must aim carefully so as not to miss our mark. We are armed only with a slingshot and the Stone of Truth. But don't underestimate our weapon, for Truth hits hard and squarely between the eyes. It paralyzes the gut. It stings sharply and jolts the senses. Many a Lyme soldier has run in fear from the Giant named Monopoly. But a few brave warriors have stood their ground, taken aim and slung the Stone of Truth. One of those valiant Lyme warriors is Dr. Joseph G. Jemsek.

Dr. Jemsek began treating Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) patients in early 1983, when he is believed to have diagnosed the first case in North Carolina. By 2006, Dr. Jemsek had cared for more than two thousand HIV/AIDS patients.

In 1998, showing gratitude for service to the HIV/AIDS community, North Carolina Governor James Hunt presented Dr. Jemsek with the Governor's Award, a Certificate of Appreciation. In 2003, Dr. Jemsek formed a non-profit that provided case management and education financial assistance to HIV/AIDS patients to help them with the cost of their treatment. Governor David Easley, who succeeded Governor Hunt, also awarded Dr. Jemsek with the Governor's World AIDS Day Volunteer Service Award in 2004.

Over the years, Dr. Jemsek and his staff were leaders in FDA clinical trial research for new therapies in HIV/AIDS, participating in almost one hundred FDA approved pharmaceutical trials, of which twenty-two became established treatment protocols for those suffering from HIV/AIDS.

In 2001, shortly after establishing the Jemsek Clinic as an HIV/AIDS clinic, one by one, another abandoned patient community approached Dr. Jemsek for help. Those suffering from Lyme Borreliosis Complex desperately sought what Dr. Jemsek had provided to his HIV/AIDS patients - an open mind, a listening ear and the ability to research and analyze the complex infections that were destroying their lives. Quite sadly however, in 2006, despite his research and philanthropic efforts, Dr. Jemsek faced political and legal battles related to his involvement with treating Lyme disease. These actions resulted in the loss of his HIV/AIDS practice, which at that time consisted of more than one thousand patients. Dr. Jemsek tried to salvage his practice to continue serving the HIV/AIDS community, but ultimately, the circumstances separated him from the patient population on which he has built his entire career, and left many of these patients without suitable options for health care. Fortunately, Dr. Jemsek's experience with the HIV/AIDS epidemic has had a long-lasting and positive impact on his current view of medicine and the way in which he now focuses his resurrected practice on those suffering the ravages of Lyme Borreliosis Complex.

Tina: Dr. Jemsek, on March 20, 2009, you hosted an event in Charlotte, North Carolina to bring awareness to Lyme disease. Would you please tell us about your awareness event and its success as such?

Dr. Jemsek: We hosted the Into the Light Gala and it was a huge success! It was a landmark evening! We came up with the idea after I attended the Unmask the Cure Gala in New York in November 2008. It was the second time I went to that event, where I had the good fortune to became acquainted with Staci Grodin, founder of the charitable foundation, Turn the Corner, which sponsored the New York Gala To my knowledge, Turn the Corner has been the largest fundraising organization for the Lyme cause in the country for the past several years. Like so many others, the Grodins were impacted by Lyme Borreliosis Complex and decided to take assertive action for positive change. Turn the Corner is head and shoulders above everyone else, both in their success and their ability to inspire, because they conduct themselves with integrity and do it for the right reasons.

So, I was inspired by Turn the Corner and felt that we should do something similar in Charlotte, not so much as a fundraiser since that requires much more infrastructure and time, but more as a major awareness campaign and a way to feature the film Under Our Skin. When I told Staci we wanted to do a gala for Lyme awareness in North Carolina and asked if her organization would be supportive, she jumped on board right away. That's one thing I love about Staci -- she agreed to help without hesitation. Turn the Corner graciously agreed not only to sponsor our Gala, but also agreed to be the surrogate charity for the event. In this way, all donations to support the Gala went to them as a charitable organization and offerings became tax deductible. In short order, I then asked National Capital Lyme, who has 2000 members from their DC area, to become a co-sponsor. They agreed, also, and it worked out great.

With our major sponsors in place, I put a team together and started by assigning our research coordinator, Michelle Thomas, to head up the Into the Light Gala committee. Michelle, along with Mark Pellin, a journalist and editor, put in hundreds of hours and made several key contacts important to the Gala, including arranging the involvement of a skilled graphic arts professional. This group was joined by my wife, Kay, and they came up with the amazing tri-fold invitation, along with the beautiful banners displayed at the event, among many other things. Very early on, we also worked closely with Kathy Fowler in DC, a media journalist with great experience in the Lyme issue and featured in the documentary. In addition, Staci generously allowed us to work with a chief staff member for Turn the Corner, Darren Port. In the end, rather quickly, we had a professional organization and marketing team that communicated regularly and functioned very well together.

Even in the beginning, I had a sense that we were going to have a successful event. We started in November, with the Gala held in March, so there wasn't a lot of time to pull it off, but I just had this calm sense that it was all going to come together. It did come together and I believe it was the time in our history when it was meant to happen. And more things like Into the Light need to happen and will happen.

The Into the Light Gala hosted over 450 people, some traveling from a great distance. It was a very powerful evening, as one can glean from the DVD overview of the Gala. In remembering the evening and looking at the DVD images, there is definitely a sense of energy, mass and purpose coming out of the event. The Gala gave us a chance to come together to support each other in spirit and have that physicality there, too. It gave us the opportunity to honor some wonderful people with a category which we termed our Courage Award. Most of the award recipients have suffered from this illness and then done extraordinary things to try to help others with the illness. Among the recipients were PJ Langhoff, author of the incredible, recently published book The Baker's Dozen and the Lunatic Fringe and Kathy Fowler, who I mentioned earlier.

We opened the doors at 6 p.m., but by 5:30 we already had about a hundred people in the lobby. The movie began around 7:15 and people hung around until midnight. We filled two theatres by using a simulcast operation. It was very exciting! I wanted to invite as many people who weren't aware of the epidemic as possible, so as to create awareness to people who can make a difference, whether it was friends of friends or business community and political leaders. Several Charlotte city council members were there, as was a representative of the Governor of North Carolina, an individual who suffered from Lyme disease years ago. The media coverage was definitely there and was particularly good for a first time event. We're going to have a professionally produced DVD made of the production by Andy Abrahams Wilson of Open Eye Pictures. You'll see that eventually. We want the photos and the DVD, in particular, to be our legacy to open doors down the road.

Jordan Fisher Smith, the park ranger portrayed in Under Our Skin, who is now working professionally as an author and lecturer, was our Master of Ceremonies. He did a wonderful job of tying the evening together. Mandy Hughes gave a moving acceptance speech on behalf of our Courage Award recipients. In another awards category, the Vision Awards, Turn the Corner Foundation, National Capital Lyme represented by their founders and leaders, Gregg and Monte Skall, and Andy Abraham Wilson, producer and director of the documentary, were all honored for their priceless contributions to promoting positive change. And everyone was blown away by the movie.

After the film concluded, I said a few words. I called on my profession to do better for its patients, to regain its mission for putting the patient first. I also called for the outing of our corrupt health insurance industry. This was an opportunity to speak in a clear and civil manner about the debacle of our health care system and the disgrace promulgated by certain physicians in power, who have exacerbated and prolonged the suffering experienced in the Lyme epidemic. I tied together the Lyme epidemic and some of the issues we're experiencing in our economy, with regard to the excesses we observe all around us, fueled by greed and arrogance. In the end, I hope everything tied in together, and I do think it really resonated with the audience. All I really did was say out loud what everyone already knew.

Tina: I do appreciate this event from a distance, because it opens doors for every one of us. Thank you for holding the Into the Light Gala and for sharing it with the readers. On a different note, I'd like to ask you for your opinion on pulpit sermons on Lyme disease that emanate from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

Dr. Jemsek: I do belong to the IDSA and it's a really excellent organization, but like any large organization, it depends on leadership, truth and integrity in leadership. Their leaders have done everything they can do to be denialists, and I think their leaders have put them on the path to perdition. The IDSA body has just been bamboozled by this 'Lyme Cabal', which consists of only one or two dozen individuals.

Tina: As a member of the IDSA and acting Treasurer of the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS), you could, under the right circumstances, act as a facilitator. You could be someone who could bridge the gap between the two organizations. It is outrageous that your attempts to do so, in the form of letters written to the IDSA about what you were seeing with Lyme disease, fell on deaf ears. This speaks volumes about the IDSA agenda.

Dr. Jemsek: I think those attempts are what got me into "trouble". In a series of letters over several weeks that began in late 2005, I communicated to them with comprehensive and referenced reviews of the arguments at hand and pleaded for change. I made it very clear to them that, not only was I concerned about my patients but also the IDSA Society, if they insisted on staying on their path. One day my letters will be public and in them can be found my statements to them that said, "You're vilified around the world for your policies, so please consider this. I'm proud to be a member of this organization, but you need to open things up." It would certainly appear that they came after me, because I was spoiling their party, and I think we'll learn much more about the ruthlessness of their actions over time.

However, I had no idea that these people and others would so ruthlessly guard and advance their agenda. And there is a sickening sense of evil connected with their actions. At any rate, the bloom is definitely off for me now. This whole experience and the actions of groups in power is now 'up close and personal' with me, and frankly still leaves me incredulous. I thought I knew a lot about human nature and it turns out I knew very little. You see, I had this wonderful medical experience in HIV/AIDS for over two decades, and I've witnessed incredible cruelty to suffering patients and I've also seen incredible kindness and giving. So, I thought that I had already seen the best and worst of human behavior before the Lyme story happened. But I never fathomed that the corporate world and their counterpart in medical politics could be as ruthless and evil as they are. They really wanted to take me out. For me, what's happened is I've learned about things that I didn't want to learn about.

Since they blew me up, I've learned about trial lawyers and lawsuits, medical boards, insurance companies, malpractice companies and academic physicians and their motivations. I didn't want to learn about any of this stuff, but now at least it's all demystified for me. Nothing rattles me too much now. Of course, there's always going to be something else to learn about, but trust me, I've learned about being in the courtroom, filing bankruptcy, foreclosure on my building and the near loss of my house. My family went through all that with me and my wife stuck with me throughout it all. But I'm just that much stronger, and I'm a big problem for them now.

Let me tell you something funny. One patient said they were watching a show late at night, Golden Girls. It was from 1985 and it was about Lyme disease. The patient was sick and tired of getting brushed off by all the doctors. But the upshot of the show was that the woman was finally diagnosed and got better, but then raised hell with a doctor in a public place saying, "You should listen to your patients!" And the same patient brought me an old magazine tear out from a home health guide, probably from Jackson, New Jersey, talking about Lyme disease and how it could be passed to the fetus, how it could be chronic and how it can require long term antibiotics. And this tear out was from 1991.

Then there was a total shift by these arrogant individuals. Sometime in '93 or '94 there was an embargo on the truth. Overnight, things turned around and white became black and vice versa. For example, in the infamous 1994 Dearborn meeting, Allen Steere pretty much turned everything around and said there was too much Lyme disease being diagnosed, and as PJ Langhoff writes in her book, they hijacked the truth and turned Lyme into junk science in order to promote their vaccine and other interests. It was all about their own motivation. It was just incredibly wrong, and we're still living with this fifteen years later.

Tina: How are doctors able to ignore ethics and put their own agenda above the patients they promised to heal?

Dr. Jemsek: As I spoke of at the Into the Light Gala, our mission has been lost in medicine. Our doctors have lost their way. I think it came about in a lot of complicated ways, such as the increasing change in the independence of the physician and their failure to invest in their own profession by integrating with all the disciplines that deliver healthcare. In other words, doctors have always had this tremendous ego, which I think is a huge protective bubble for them. Unfortunately, I think it is unearned and misplaced ego. And what that does is create a situation wherein if the doctor doesn't understand something, they make the patient the problem. It's kind of dummied-down medicine to the point that, if they don't understand or listen to what a patient with complex medical issues tells them, they put it in one of three big buckets-fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue or crazy. That's really sad because life and medicine are more complicated than that.

One of the things I said in my speech is that arrogance trumps reason. So, if you are arrogant for whatever reason, it totally corrupts the doctor-patient relationship. In addition, the doctors have been brought under pressure economically because of the restructure of medicine with the HMO's, Medicare and paperwork. They have to jump through many hoops to satisfy the leaders of American health, the insurance companies.

I really am very sad about doctors having lost their profession. We're now working for insurance companies and hospitals. Instead of turning our energy outward to try to change things, we often turn it inward against each other. Often doctors are jealous of the one who is more creative, disagrees, who has new ideas, who makes more money or who seems to be more popular. As a group, we as doctors are really small-minded people. And the chasm between patient and doctor has been magnified since we've gone full bloom in the information age, so that patients have access to information they didn't have in the past.

Tina: Unfortunately, this occurs at a time when chronic infections are rampant. You've certainly made your case for something you expressed in your speech at the Into the Light Gala, when you said, "The delay in recognizing our nation's Lyme epidemic presents a prime example of our broken health care system. The way in which a society deals with a marginalized population is the signature and indelible stamp of that society's character…give the U.S. health system an F grade for its work here."

Dr. Jemsek: Yes, we do a horrible job of dealing with chronic illness. In a strange way, the Lyme epidemic may be the tipping point for making significant change, because it is so painful and so complex that it's going to force us to finally work it out. It's not going away, no matter how long Gary Wormser holds his breath. We need to think about the whole picture of interaction and interrelationship of chronic infection and epidemiologic control and examine why we have so many other co-morbidities. Could chronic infections be at the root of a lot of our rheumatologic and other diseases?

Tina: Does what you refer to as Lyme Borreliosis Complex or LBC include Lyme and co infections?

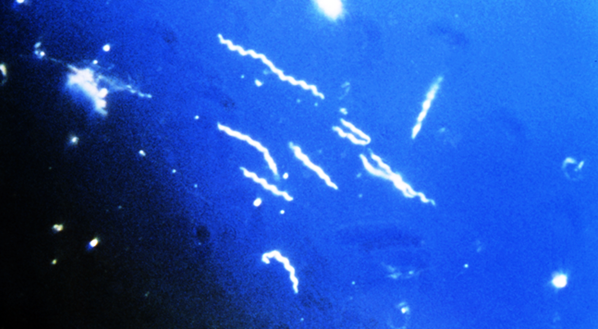

Dr. Jemsek: Yes. You see, one thing I noticed with HIV early on, is that we have a different paradigm in that the virus replicates every thirty minutes or so. With LBC we have what we call pleomorphism and polymorphism. Pleomorphism has to do with different life forms and polymorphism has to do with different genomic patterns within the same species. So, as organisms evolve and multiply in a host, they're not carbon copies.

When I talk about the Lyme Complex, what I mean is that I realized early on that our patients are multiply infected. Because I came from an AIDS background, I saw the immune system melt. Although we have a different model with Lyme Borreliosis Complex, the concepts are similar. And what happens is that the immune system melts and we get opportunistic infections that come up after a while. What we saw in the early days of HIV medicine was absolutely bizarre back in the early 80's, because we only read about these things in textbooks. Like,-pneumocystis pneumonia, for example. That was something only kids with leukemia at St. Jude's Hospital in Memphis got after they had received high-dose steroids for months. Or, it was also seen in the malnourished in Auschwitz. But then we started seeing this regularly, and it became by far the most common life-threatening infection in HIV/AIDS.

We also saw the yeast infections and shingles (herpes zoster) come on in twenty year olds. We saw people go blind from cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections. We saw mycobacterium avium complex in blood cultures and as sheets of mycobacterium in stool samples. We saw bizarre stuff, but after a while, it all started to fit into a big pattern. And so, after you see a few hundred patients, you start to realize that when you see a certain CD4 count, the patient's going to get this or that. And we started to get better at that. And we realized how many other systems were affected whether they be metabolic, hormonal, malignancies and so forth.

With Lyme disease, there is absolutely no reason to believe that there are simple answers and simple solutions. When people are really sick, they are multiply infected. And I learned a lot from the animal studies, which indicate that if you're infected with Lyme, you're going to get weak and dizzy. But if you add babesia or bartonella, the animal will die. So I learned that and in my own practice, I started looking for signs to tell me why people relapse or do not get well. And in the early years, I came to the conclusion that they're multiply infected, and you have to treat it as a group or conglomeration of infections and regard it as an immune suppressive illness. In other words, we have a Lyme Borreliosis Complex syndrome and a multisystemic chronic illness.

Tina: In your experience with Lyme patients, have you seen anyone who has exhibited AIDS-type symptoms from immunosuppression?

Dr. Jemsek: Well, I had some AIDS patients who had Lyme. And you know what? The Lyme was worse on the patient.

Tina: Do you currently treat any HIV patients?

Dr. Jemsek: No, I pretty much had to close it down because of the insurance cancellation and lawsuit against me. When that happened, when the dominant insurance company in North Carolina took away our contract, it spelled the end of my HIV practice. When the insurance company sued me, I lost any reasonable chance for a turnaround. What was clearly vicious and premeditated is that they were just trying to take me out; they didn't have to sue me nine months after the news of a medical board review. That was a kill shot, and as I said, they were just trying to take me out.

Basically, their actions assured that a thousand HIV patients were put out on the street. And we had one of the largest HIV practices in the U.S. and the world, and we were going to double our patient population in four years. We did this with a high standard of practice and very good care in a really good setting. It was our dream to do that. As I say on my website, since there were six practitioners seeing new Lyme patients, we probably also had the largest Lyme and tick-borne illness practice in the country. In late 2005, we were seeing eighty to one hundred new patients a month for possible tick-related illness.

Our case is still ongoing and it will probably take another two to three years to resolve. History will judge us for what we've tried to do and I'm fine with that. I don't totally understand it and I don't try to understand it anymore, but there's a reason I've been put in this position. I also have a sense that people are attracted to my story because Americans like underdogs and resiliency. So, I believe that there's a reason I lost my HIV practice, but now I have a new love in medicine and an incredible challenge.

One of the real tragedies about this epidemic is to think about all the sick people who are clueless about their illness and lead wasted lives, or worse, know their illness and can't access care. And then to consider the sheer size of the epidemic is simply staggering. Even with more efficient models of treatment at our clinic, it still takes a couple of years to get people really better. So, anyone can do the math. It's horrible to consider, but this epidemic can bring our nation to it knees.

The Lyme epidemic is going to forever change how we look at chronic illness. We're going to have to get out of the patch-and-pay model that we have and get into real answers. And if we were all really pulling together and trying hard to get answers for complex patients, we would be well on our way to making significant progress. As it is, the politicization of this epidemic and the corporatization of health care have literally put us twenty years behind, and in the end, this indifference to the human condition will have victimized millions.

Tina: Dr. Jemsek, what is your approach to patients and your method for treating Lyme Borreliosis Complex?

Dr. Jemsek: With regard to my approach to patients, I am unable to accept insurance, so there is a financial challenge for patients, which I regret and always appreciate. Almost all patients completely understand this situation, and we do everything we can to help with HICFA forms for insurance filing and so forth. But we all know that health insurers are terrified of the 'black box' which LBC represents, and that their business model is essentially 'anti-patient'.

There is also a travel challenge in most cases, because I see patients from all over the country and quite a few from Europe and other continents. For example, I've had patients come from Russia, Lebanon and Australia to visit the clinic in South Carolina. I've had a dozen to fifteen or more patients come from the Scandinavian countries, as well.

Tina: So despite all the problems forced upon you, patients still come to see you for help.

Dr. Jemsek: Yes, because it's a worldwide epidemic. In fact, we get emails from patients, several per week on average asking, "Can you help me?" People are desperate. It really breaks my heart. I currently only see Borreliosis patients, but I'm seeing sicker patients than I've ever seen before.

Tina: How does the office visit unfold when patients see you for an appointment?

Dr. Jemsek: A new patient intake is a two-hour visit. We ask that the patients complete a clinical medical history form, and they typically bring in an inch or two of records which we review thoroughly. I usually start the patient interview with the question, "Are you doctor referred, or are you here with your doctor's approval or understanding?' Then I ask the patient which doctors they want copied on my consultative note. Some patients say none, some want several doctors copied, and some decide later, so we're happy to do that for them and really encourage the communication.

For as long as I can remember, I have made a practice of providing a copy of the consultative note to each patient, so the patient gets our whole summary with recommendations right away, and of course, I copy any physician who referred the patient or to whom the patient wishes records be sent. Ideally, we want exhaustive but well-organized reviews up front, because if you don't get it on the first or second visit, you likely will never have a history that serves the patient well. In most cases, we set several actions in motion immediately after the visit, and it really isn't until later when laboratory tests and procedures are concluded, that we get a more complete picture. These are extensive documents that I create.

Tina: That's a great help to someone with cognitive dysfunction.

Dr. Jemsek: Exactly. Everyone's from somewhere else, so if someone's on IV therapy, for example, they have to have a collaborating physician at home, no exceptions. And if the patient is going on an oral antimicrobial regimen, we still very much encourage collaboration with a local physician, but we don't demand it.

Patients always have the discretion of taking their records and going to the next physician or finding a physician. I am currently able to interview about five new patients a week on average. That's about all I can do. On the first follow up visit or with a patient that I haven't seen in a year or two, we devote forty-five minutes. On a routine scheduled office appointment, the scheduled time is thirty minutes. So as you can see in that way, from the time allotments, I can only see ten to fourteen patients a day max. If I see more than one new patient a day, it's a really long day.

I just think that doing as much up front and doing it as thoroughly as possible pays tremendous dividends in terms of patient care, organization, and mutual understanding of what the goals are. We're booked out about four months now, but the consistent trend continues to be for this period to grow longer. We have approximately seventy-five new patients on the waiting list and the list is growing every day. However, very soon I intend to bring in two nurse practitioners, and that should significantly expand our new patient intake. As appropriate, we're going to be able to charge considerably less for the nurse practitioner visits, which will help our patients access the clinic, but I'm going to promise that I will always see the patient on the next visit.

Tina: What about your clinical staff and other areas of practice?

Dr. Jemsek: I am up to about fifteen employees now, whereas at the Jemsek Clinic in 2005 I had seventy employees serving the twin epidemics of HIV/AIDS and LBC. Some of those folks were research PhDs and we really miss them, and not that we are semi-resuscitated, but we're going to start our research again. I recently brought back some really outstanding people who worked with us before. My head clinical research RN is coming back, along with another RN whom I worked with in infection control when I was the epidemiologist at Carolina Medical Center years ago. With these outstanding individuals back on board, we're going to start doing respective chart reviews and thorough data collection. I'm also teaming up with a Ph.D. in chemical engineering who's incredibly bright and very well-connected, and has this wonderful model for database collections, among other things.

Our research efforts will follow two or three different paths. One path is basic data collection and the other paths will involve much more sophisticated research, both clinical and basic science in orientation. This will require collaboration with a number of scientists and we're confident we can make this happen. What our clinic provides, above all, is the patient population and an excellent knowledge of which questions to ask. The real trick is knowing how to prioritize what is most useful now and what can wait, since there are literally thousands of potential projects that need to be explored. I'm very anxious to turn over some of this process to people who are much smarter than me who can run with it. It's just incredible, because we're at the beginning of a new frontier. It's as though we're starting all over again. The only advantage we have is that we have the experience of HIV/AIDS, and if this research project ever gets capitalized, we can jump start this thing.

We will use the HIV/AIDS epidemic as a model, although as most recall when it first started, no one was interested in all the gays who were dying. But soon it became a national agenda, things picked up and the government did do the right thing by starting the ACTG groups. That was a really smart thing to do. They asked the clinical trial, basic science questions and did the research, the grunt work so to speak. Then pharmaceuticals and NIH became heavily involved, and of course they brought in money, and it became a multi-billion-dollar enterprise, attracting the best minds in infectious diseases.

So really, at least from a scientific point of view, once the commitment is made, the jump to understanding LBC should come from a tremendous platform built on the back of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, or at least it should work that way. On the realistic side, however, my research associate made the remark that a seasoned immunologist recently admitted to him that we know next to nothing when it comes to most chronic illnesses. And really, nothing is as easy as I have just described, so it may take decades to fully understand the epidemiology, molecular biology and nature of the disease states associated with LBC.

I expect my experience in HIV/AIDS and LBC to parallel each other, if I am around long enough. In HIV/AIDS, I came from one world where I grew up and spent the first decade or more of my experience dealing with the human aspects of a deadly disease, and so I got a crash course during part of my career getting in touch with my own mortality and who I was as a physician. Then, during the next decade, as the money rolled out and thousands more became involve in research and treatment, the science was simply incredible.

I was involved with HIV and attending and presenting data at very well-funded meetings and that sort of thing. Then I went from that world to the Lyme world, which in the beginning was pictures of raccoons and deer ticks on the wall at a meeting in some New Jersey lodge, lectures on pulling out amalgams as a cure and saying that was what was causing all your troubles and listening to lecturers who had never used a PowerPoint presentation. It freaked me out.

Tina: Are you aware of any research that's currently being performed or are you planning to do any research with regard to sexual transmission of Lyme disease?

Dr. Jemsek: No, not in the beginning. That's just too hot to handle. But I'll tell you something interesting about sexual transmission. Every married couple asks me that question. It's at the top of the list. "Can I pass this on?" So, if something is that high up in the consciousness, why is it that we've never done a study? It's obvious the CDC has an agenda to avoid this issue as long as possible. People are intimidated from even mentioning the possibility. What I tell people is that, between sex and ticks, we're all infected. And I believe that. I think the spirochete is part of our endogenous flora. Our biosphere has sort of made that transition, and I think we're all infected. So, we have this whole new paradigm in medicine, this whole new jump-shift logic.

And even though people don't smoke as much and we don't have as many smoking-related deaths, we have way, way too much chronic illness. I think that between these new infections that have emerged over the last several decades, which are relatively new in terms of penetrating the society, and what we're doing to the environment, we're in for trouble. I can't even bear it. Intuitively, we know the stuff we've done cannot be good for us, and it can only go one way -- it's got to be bad to some level. So between all the chemicals we use in our environment and the chronic illness, it's a whole new moving paradigm. Right now, all we do is just treat symptoms with very expensive drugs and shut down the immune system. What if some of these things are reversible?

Here's the ugly fact and the ugly truth: This disease is a TSUNAMI. The disease is so prevalent and it's affecting so many decision-makers and their families, that this will force the change. And I predict that in the next year or so we're going to get some big names involved. Congressmen and CEO's are being affected, and I've seen doctors and their patients for this illness, so it's bound to happen. And at some point somebody with some outrage will step up and there will be questions answered. I think the film Under Our Skin has done more than anything before it, or anything that may come, to change the consciousness of America about Lyme disease. We all get comfortably numb with what's going on, but not for long, and we can't be indifferent and ignore it anymore.

We need to change the way we approach medicine, and it's frightening that we're talking about nationalized health care. As horrible as our current health care system is, with nationalized health care, medicine would be a death knell for any hope in the revolution needed for diagnosis and treatment of LBC and other chronic illnesses.

Tina: Do you ever see acute Lyme disease infection?

Dr. Jemsek: No, I essentially only see early accelerated illness or longstanding illness. I check to see if the patient has a defined tick event, with or without a rash, and has an illness compatible with an evolving, persistent, neurocognitive and musculoskeletal illness occurring within a few weeks of the recognized bite. If so, then they pretty much have a deeply embedded infection, a chronic illness, and will need to be treated like anyone else with chronic illness. Or, I'll see someone who got bitten three months ago and they're sick, going from doctor to doctor, and they manage to get an appointment because they have an awareness.

Mostly, I see chronic illness. When I get some data together, I'll be able to tell you the mean duration of illness, or give it a good try. But even more fundamentally, when you go back to determine how this disease activates, I think most of my patients are infected well ahead of the defining or recognized clinical event and sustained illness is generally associated with a tipping point from a life stressor. This may or may not be related to a tick bite or to a defined tick event. This is oftentimes related to a prolonged period of stress, another illness, physical trauma or childbirth, etc. This happens because, even though we can't measure it, there is a clear and certain immunologic frailty associated with subacute infection with Bb and co-pathogens. There's a tipping point and sometimes people stair step.

What I tell my patients to help them understand is that we're trapped by this illness in two ways. One is by the biologic nature of the illness, but we're also trapped by our health care system. So, when people get really sick, there's no way out. I see early accelerated illness, and by that time I consider the infection to be embedded. Spirochetes get in the brain within thirty minutes. By the way, IDSA has no basis for their guidelines. This illness is going to force people to 'IQ up' with regard to our approach to this disease and to medicine in general. We need to put medicine back on a cerebral and compassionate plane that works for our patients.

Tina: What are some of the most important clinical observations and treatment recommendations you have made with regard to Lyme Borreliosis Complex?

Dr. Jemsek: What I learned a few years ago is that you don't have to treat every day. And with my HIV and infectious disease background, I learned the virtues of combination therapies. When you're dealing with a complex group of infections, there's no one drug that's going to satisfactorily handle the infection unless you're not that sick. It's all about putting your immune system back in charge. And to the extent that you can eliminate the source of the immunosuppression and your immune system recovers, you've done your job.

Everyone who's trapped by this illness needs nutritional support, metabolic support, and they need antibiotics. Some people are negative about antibiotics, but you can't evaluate antibiotic therapy in a vacuum or as 'all the same'…that's patently intellectually dishonest. We are, after all, treating multiple, stubborn infections in an immuno-compromised host where, by definition, the immune system cannot handle the problem. And our goal is not to see how many days of antibiotics we can administer, but to administer the fewest days needed in order to restore immunologic control. Towards that end, we need to understand the triggers to keep patients out of situations that are going to perpetuate the patient's chronic illness and/or make it unwise to attempt therapy until these destabilizing stressors are reduced, whether the stressor is as basic as a bad support system or involve psychiatric, pain or sleep issues.

In treatment models, I've learned that pulsing makes sense, and I think everyone who's really sick has multiple infections. When I treat the three major infections, which are Borrelia, Bartonella and Babesia, and do that in a certain sequence and in a certain combination, people get better. And I think it's very important for people to go off therapy on an intermittent basis for one or two weeks at a time. Those windows are very important times to see how much immunologic security they have. Patterns develop, and the better the patient is, the longer they can go off drugs. For many years now, we have learned to pulse combination antimicrobial medications in certain patterns, and I have modified our clinical approach from learning the tempo of the disease.

Often you learn more about your patient when they're off treatment than you learn when they are on active treatment. These 'holidays' provide valuable windows for observation and after a time, you learn that cycles of therapy and the way they are sequenced show reproducible patterns of response. You also learn a lot from aspects of the treatment period, whether it's being on treatment, when it's the time to take Flagyl, and certainly the time that they're off treatment is a very important window for you to see how the patient is doing immunologically. And once you learn patterns and understand them, then you know when to intervene and when to back off. One of my patients said, "You're doing a dance with this disease, aren't you?" That's not a bad analogy.

I learned a long time ago that the most common reason for people not to get better is inadequate treatment of co-infections. It's very important to address the co-infections and to do so in an overlapping way, so you're not just treating one thing and then going on to treat something else. I only treat three days a week whether it's oral or IV, and have been doing it this way for at least five years, and exclusively this way for almost three years. And on all my programs, I give a week off of therapy on average every two to four weeks. I don't do it so much at the beginning, but after we get into it, patients get immunologically revved up.

In treating patients at the clinic, we are constantly striving for a balance point in terms of clinical efficacy and manageable toxicity, the latter being an inevitable sidebar to the highly immunogenic and inflammatory lipoprotein storm we see with Borrelia lysis. When the immune system activates, a patient can actually get more toxic, so we have to balance that. It's part of the art of medicine in terms of learning how to balance the toxicity generated and the fact that the patients need to detox. And I prefer to think there's a 'back door' to this illness as regards to the detoxification issues. If the 'back door' is closed, patients may remain unwell for protracted periods. Without question, there are considerable variations in the segment of the population with this illness who are going to be very sick, in terms of the ability to detoxify. This, in fact, may be as critical to outcomes as the infectious load and immunologic/genomic factors. That's the way it was with HIV, too, in a sense.

Tina: Dr. Jemsek, you are a beacon of light, a hero, to many of us in the Lyme community. You are thought of in this way, because you have established yourself as a Lyme-literate physician who is able to guide patients back to health. In addition, you have faced your difficult experiences with the North Carolina Medical Board and Blue Cross/Blue Shield with a calm demeanor and resolute determination. What has helped you to remain centered and focused during the challenges you have faced with all these legal battles?

Dr. Jemsek: Thank you for those kind remarks, Tina. My response would be family and patients. I get boatloads of affirmations every day. The other day I got four hugs, so how can you not like doing this? I really mean this. We can help people in such a profound way just by our ability to understand. It all starts with listening. I honestly didn't always have an ear for listening, but I learned this skill in caring for the very ill with HIV/AIDS. When Lyme patients first walked through my door, they said, "I hear you treat Lyme disease." And I said, "Well, yeah. So what?" But they kept coming, and believe me, I didn't get it for a long, long time. It took me about six to eight months to really understand.

As a doctor, you have an understanding about how patients are trying to paint their picture for you, and even if you listen, you may not understand it the first or second time. But when you hear it enough, you begin to form your own belief constructs and interpretation of it. And then you get reinforced as your impressions and concepts are molded. In many ways, it's like learning a new language, a language with a new alphabet, like Chinese or Arabic. And you don't learn it overnight. But the patients learn it and we talk in this strange new way with terms not found in modern medical text. And if another doctor's in the room and is listening, they don't know what the heck we're talking about. The patients get it, but to state the obvious, a lot of the doctors become very uptight about not understanding, and the patient then becomes the problem.

So, if doctors would just let their hair down a little bit and take a big dose of humility and honesty, they'd be so much happier. It would set them free. You know, I never worry about not knowing something any more. I worry about those who feel they must always be right. AIDS taught me that, because we didn't know anything. We were up to our asses in alligators, and we were just trying to do what we could. It was a very creative period for me and a lot of other people. But some people look at you like a reckless cowboy when you do something different, because it makes them uncomfortable, even if they have no answer and even if the patients benefit.

When it comes to my patients, I always ask, "What made them better? Why did they get better?" We can grow and evolve this way, as our patients are our ultimate laboratory for progress. And so now, as complex as Lyme patients are with their 150 complaints, their symptoms and physical findings now make recognizable patterns. And I can see the patterns, and I'm very comfortable with all these complex issues. But I realize how much we still have to learn, and that's really what's fascinating. I'm having a certain amount of success, and I'm learning what questions to ask. But my constraints, of course, are time and money in trying to get answers to everything.

And I see so many neurological manifestations in LBC and I use more seizure drugs than almost anybody, because that's what I have to do. I have a whole plate of medications I use in terms of seizure, potent antidepressants and mood modifying drugs. You just have to. But I can tell you this -- I think that this is going to be fascinating as this thing unravels. And I'm telling you, people are going to discover things that I've known in my head and other doctors, like Richard Horowitz and Bernie Raxlen, have known implicitly for years. We've all known about stuff that hasn't been written down yet, all sorts of strange clinical facts. In five or ten years, they're going to say "Oh well. This happens and blah blah blah." And we're all going to say, "Well, yeeeeaaaah."

For example, I saw some case reports from Europe on ocular palsies being prominent as the presenting sign in early or advanced Lyme. And these were case reports, but on some clinic days, none of my patients can coordinate their eye movement. It's things like that that I know already from the clinical setting. The complexity of the illness has prompted many of us to learn a great deal more about neurology, endocrinology and dermatology. And while I know that the doctors in these specialties that I've mentioned are incredibly bright, they seem sort of frozen and locked into their ideology. And the more intense the ideology, the more hostile the specialist becomes when confronted with something not in their comfort zone, or something which challenges them. Doctors have lost control of their profession in a mission lost, and the prevailing attitude of false pride is part of the pathology we see contributing to the failure of today's medical system. As I stated in my speech at the Into the Light Gala, arrogance trumps reason every time. It's sad really, and doctors need to break out from this or be eternally miserable, because this epidemic is going to make fools of a lot of arrogant physicians.

You have to put yourself in a position to understand that it's okay to say that you don't know something. What's really important is that you continue to try to learn. If you do that, it all comes together. Patients really get that. Then you don't have posturing and antagonism that creates a chasm. It's just so much easier to say "I don't know, but let's learn. But here's what I do know about this." I know doctors are frustrated, but they turn their anger inward instead of looking at the real problems and getting together to try to bring the profession back where it should be. And if you don't have a passion for it, get out of medicine.

In particular, I think the infectious disease doctors have been hoodwinked, in part because their source of information has been compromised by the Lyme Cabal. The ID docs, for some reason, have a characteristic that I just don't understand. More than any other specialty in the LBC debate, they are consistently rigid. You just cannot be rigid, for we need to just admit that we only know a fraction of a percent of what we need to know about the human body and medicine. Much of what we know now is going to change anyway. So, you just try to keep learning and if you have success, you try to understand your success and understand your failures, too. And if you can do that, then you grow as a doctor and you get so much satisfaction out of seeing patients.

When you get into this ritualistic practice, like having a certain algorithm for treating this or treating that, how boring. I acknowledge that we must have some guidelines and some semi-rigidity to our beliefs and the way we practice medicine, of course, but always understand that we need to grow and learn every day when we go to work. Most doctors will view a patient based on their own experience and their empiricism rather than what's printed in a textbook, I'll tell you that. I mean the really good ones.

My message to doctors is "Get real!" Learn some humility, be honest, and it will set you free. Then you will be the kind of doctor you wanted to be when you started out from day one. But if you cover yourself up with false pride and arrogance, then you're doomed. It doesn't work, never has, never will.

The Lyme disease community is an army with limited resources, limited strength and the limited ability to have our voices heard amid the roar of the mighty Giant. We are like young David from days of old-facing formidable foes which show no mercy or compassion for our plight, but only disdain and contempt for our resilient survival. We are painfully experiencing the dominance of government agencies, the wealthy insurance industry and influential medical societies, all of which wield power capable of crushing anything and anyone who stands in the path of their objectives.

In defending our position, the Lyme community must aim carefully so as not to miss our mark. We are armed only with a slingshot and the Stone of Truth. But don't underestimate our weapon, for Truth hits hard and squarely between the eyes. It paralyzes the gut. It stings sharply and jolts the senses. Many a Lyme soldier has run in fear from the Giant named Monopoly. But a few brave warriors have stood their ground, taken aim and slung the Stone of Truth. One of those valiant Lyme warriors is Dr. Joseph G. Jemsek.

Dr. Jemsek began treating Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) patients in early 1983, when he is believed to have diagnosed the first case in North Carolina. By 2006, Dr. Jemsek had cared for more than two thousand HIV/AIDS patients.

In 1998, showing gratitude for service to the HIV/AIDS community, North Carolina Governor James Hunt presented Dr. Jemsek with the Governor's Award, a Certificate of Appreciation. In 2003, Dr. Jemsek formed a non-profit that provided case management and education financial assistance to HIV/AIDS patients to help them with the cost of their treatment. Governor David Easley, who succeeded Governor Hunt, also awarded Dr. Jemsek with the Governor's World AIDS Day Volunteer Service Award in 2004.

Over the years, Dr. Jemsek and his staff were leaders in FDA clinical trial research for new therapies in HIV/AIDS, participating in almost one hundred FDA approved pharmaceutical trials, of which twenty-two became established treatment protocols for those suffering from HIV/AIDS.

In 2001, shortly after establishing the Jemsek Clinic as an HIV/AIDS clinic, one by one, another abandoned patient community approached Dr. Jemsek for help. Those suffering from Lyme Borreliosis Complex desperately sought what Dr. Jemsek had provided to his HIV/AIDS patients - an open mind, a listening ear and the ability to research and analyze the complex infections that were destroying their lives. Quite sadly however, in 2006, despite his research and philanthropic efforts, Dr. Jemsek faced political and legal battles related to his involvement with treating Lyme disease. These actions resulted in the loss of his HIV/AIDS practice, which at that time consisted of more than one thousand patients. Dr. Jemsek tried to salvage his practice to continue serving the HIV/AIDS community, but ultimately, the circumstances separated him from the patient population on which he has built his entire career, and left many of these patients without suitable options for health care. Fortunately, Dr. Jemsek's experience with the HIV/AIDS epidemic has had a long-lasting and positive impact on his current view of medicine and the way in which he now focuses his resurrected practice on those suffering the ravages of Lyme Borreliosis Complex.

Tina: Dr. Jemsek, on March 20, 2009, you hosted an event in Charlotte, North Carolina to bring awareness to Lyme disease. Would you please tell us about your awareness event and its success as such?

Dr. Jemsek: We hosted the Into the Light Gala and it was a huge success! It was a landmark evening! We came up with the idea after I attended the Unmask the Cure Gala in New York in November 2008. It was the second time I went to that event, where I had the good fortune to became acquainted with Staci Grodin, founder of the charitable foundation, Turn the Corner, which sponsored the New York Gala To my knowledge, Turn the Corner has been the largest fundraising organization for the Lyme cause in the country for the past several years. Like so many others, the Grodins were impacted by Lyme Borreliosis Complex and decided to take assertive action for positive change. Turn the Corner is head and shoulders above everyone else, both in their success and their ability to inspire, because they conduct themselves with integrity and do it for the right reasons.

So, I was inspired by Turn the Corner and felt that we should do something similar in Charlotte, not so much as a fundraiser since that requires much more infrastructure and time, but more as a major awareness campaign and a way to feature the film Under Our Skin. When I told Staci we wanted to do a gala for Lyme awareness in North Carolina and asked if her organization would be supportive, she jumped on board right away. That's one thing I love about Staci -- she agreed to help without hesitation. Turn the Corner graciously agreed not only to sponsor our Gala, but also agreed to be the surrogate charity for the event. In this way, all donations to support the Gala went to them as a charitable organization and offerings became tax deductible. In short order, I then asked National Capital Lyme, who has 2000 members from their DC area, to become a co-sponsor. They agreed, also, and it worked out great.

With our major sponsors in place, I put a team together and started by assigning our research coordinator, Michelle Thomas, to head up the Into the Light Gala committee. Michelle, along with Mark Pellin, a journalist and editor, put in hundreds of hours and made several key contacts important to the Gala, including arranging the involvement of a skilled graphic arts professional. This group was joined by my wife, Kay, and they came up with the amazing tri-fold invitation, along with the beautiful banners displayed at the event, among many other things. Very early on, we also worked closely with Kathy Fowler in DC, a media journalist with great experience in the Lyme issue and featured in the documentary. In addition, Staci generously allowed us to work with a chief staff member for Turn the Corner, Darren Port. In the end, rather quickly, we had a professional organization and marketing team that communicated regularly and functioned very well together.

Even in the beginning, I had a sense that we were going to have a successful event. We started in November, with the Gala held in March, so there wasn't a lot of time to pull it off, but I just had this calm sense that it was all going to come together. It did come together and I believe it was the time in our history when it was meant to happen. And more things like Into the Light need to happen and will happen.

The Into the Light Gala hosted over 450 people, some traveling from a great distance. It was a very powerful evening, as one can glean from the DVD overview of the Gala. In remembering the evening and looking at the DVD images, there is definitely a sense of energy, mass and purpose coming out of the event. The Gala gave us a chance to come together to support each other in spirit and have that physicality there, too. It gave us the opportunity to honor some wonderful people with a category which we termed our Courage Award. Most of the award recipients have suffered from this illness and then done extraordinary things to try to help others with the illness. Among the recipients were PJ Langhoff, author of the incredible, recently published book The Baker's Dozen and the Lunatic Fringe and Kathy Fowler, who I mentioned earlier.

We opened the doors at 6 p.m., but by 5:30 we already had about a hundred people in the lobby. The movie began around 7:15 and people hung around until midnight. We filled two theatres by using a simulcast operation. It was very exciting! I wanted to invite as many people who weren't aware of the epidemic as possible, so as to create awareness to people who can make a difference, whether it was friends of friends or business community and political leaders. Several Charlotte city council members were there, as was a representative of the Governor of North Carolina, an individual who suffered from Lyme disease years ago. The media coverage was definitely there and was particularly good for a first time event. We're going to have a professionally produced DVD made of the production by Andy Abrahams Wilson of Open Eye Pictures. You'll see that eventually. We want the photos and the DVD, in particular, to be our legacy to open doors down the road.

Jordan Fisher Smith, the park ranger portrayed in Under Our Skin, who is now working professionally as an author and lecturer, was our Master of Ceremonies. He did a wonderful job of tying the evening together. Mandy Hughes gave a moving acceptance speech on behalf of our Courage Award recipients. In another awards category, the Vision Awards, Turn the Corner Foundation, National Capital Lyme represented by their founders and leaders, Gregg and Monte Skall, and Andy Abraham Wilson, producer and director of the documentary, were all honored for their priceless contributions to promoting positive change. And everyone was blown away by the movie.

After the film concluded, I said a few words. I called on my profession to do better for its patients, to regain its mission for putting the patient first. I also called for the outing of our corrupt health insurance industry. This was an opportunity to speak in a clear and civil manner about the debacle of our health care system and the disgrace promulgated by certain physicians in power, who have exacerbated and prolonged the suffering experienced in the Lyme epidemic. I tied together the Lyme epidemic and some of the issues we're experiencing in our economy, with regard to the excesses we observe all around us, fueled by greed and arrogance. In the end, I hope everything tied in together, and I do think it really resonated with the audience. All I really did was say out loud what everyone already knew.

Tina: I do appreciate this event from a distance, because it opens doors for every one of us. Thank you for holding the Into the Light Gala and for sharing it with the readers. On a different note, I'd like to ask you for your opinion on pulpit sermons on Lyme disease that emanate from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

Dr. Jemsek: I do belong to the IDSA and it's a really excellent organization, but like any large organization, it depends on leadership, truth and integrity in leadership. Their leaders have done everything they can do to be denialists, and I think their leaders have put them on the path to perdition. The IDSA body has just been bamboozled by this 'Lyme Cabal', which consists of only one or two dozen individuals.

Tina: As a member of the IDSA and acting Treasurer of the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS), you could, under the right circumstances, act as a facilitator. You could be someone who could bridge the gap between the two organizations. It is outrageous that your attempts to do so, in the form of letters written to the IDSA about what you were seeing with Lyme disease, fell on deaf ears. This speaks volumes about the IDSA agenda.

Dr. Jemsek: I think those attempts are what got me into "trouble". In a series of letters over several weeks that began in late 2005, I communicated to them with comprehensive and referenced reviews of the arguments at hand and pleaded for change. I made it very clear to them that, not only was I concerned about my patients but also the IDSA Society, if they insisted on staying on their path. One day my letters will be public and in them can be found my statements to them that said, "You're vilified around the world for your policies, so please consider this. I'm proud to be a member of this organization, but you need to open things up." It would certainly appear that they came after me, because I was spoiling their party, and I think we'll learn much more about the ruthlessness of their actions over time.

However, I had no idea that these people and others would so ruthlessly guard and advance their agenda. And there is a sickening sense of evil connected with their actions. At any rate, the bloom is definitely off for me now. This whole experience and the actions of groups in power is now 'up close and personal' with me, and frankly still leaves me incredulous. I thought I knew a lot about human nature and it turns out I knew very little. You see, I had this wonderful medical experience in HIV/AIDS for over two decades, and I've witnessed incredible cruelty to suffering patients and I've also seen incredible kindness and giving. So, I thought that I had already seen the best and worst of human behavior before the Lyme story happened. But I never fathomed that the corporate world and their counterpart in medical politics could be as ruthless and evil as they are. They really wanted to take me out. For me, what's happened is I've learned about things that I didn't want to learn about.

Since they blew me up, I've learned about trial lawyers and lawsuits, medical boards, insurance companies, malpractice companies and academic physicians and their motivations. I didn't want to learn about any of this stuff, but now at least it's all demystified for me. Nothing rattles me too much now. Of course, there's always going to be something else to learn about, but trust me, I've learned about being in the courtroom, filing bankruptcy, foreclosure on my building and the near loss of my house. My family went through all that with me and my wife stuck with me throughout it all. But I'm just that much stronger, and I'm a big problem for them now.

Let me tell you something funny. One patient said they were watching a show late at night, Golden Girls. It was from 1985 and it was about Lyme disease. The patient was sick and tired of getting brushed off by all the doctors. But the upshot of the show was that the woman was finally diagnosed and got better, but then raised hell with a doctor in a public place saying, "You should listen to your patients!" And the same patient brought me an old magazine tear out from a home health guide, probably from Jackson, New Jersey, talking about Lyme disease and how it could be passed to the fetus, how it could be chronic and how it can require long term antibiotics. And this tear out was from 1991.

Then there was a total shift by these arrogant individuals. Sometime in '93 or '94 there was an embargo on the truth. Overnight, things turned around and white became black and vice versa. For example, in the infamous 1994 Dearborn meeting, Allen Steere pretty much turned everything around and said there was too much Lyme disease being diagnosed, and as PJ Langhoff writes in her book, they hijacked the truth and turned Lyme into junk science in order to promote their vaccine and other interests. It was all about their own motivation. It was just incredibly wrong, and we're still living with this fifteen years later.

Tina: How are doctors able to ignore ethics and put their own agenda above the patients they promised to heal?

Dr. Jemsek: As I spoke of at the Into the Light Gala, our mission has been lost in medicine. Our doctors have lost their way. I think it came about in a lot of complicated ways, such as the increasing change in the independence of the physician and their failure to invest in their own profession by integrating with all the disciplines that deliver healthcare. In other words, doctors have always had this tremendous ego, which I think is a huge protective bubble for them. Unfortunately, I think it is unearned and misplaced ego. And what that does is create a situation wherein if the doctor doesn't understand something, they make the patient the problem. It's kind of dummied-down medicine to the point that, if they don't understand or listen to what a patient with complex medical issues tells them, they put it in one of three big buckets-fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue or crazy. That's really sad because life and medicine are more complicated than that.

One of the things I said in my speech is that arrogance trumps reason. So, if you are arrogant for whatever reason, it totally corrupts the doctor-patient relationship. In addition, the doctors have been brought under pressure economically because of the restructure of medicine with the HMO's, Medicare and paperwork. They have to jump through many hoops to satisfy the leaders of American health, the insurance companies.

I really am very sad about doctors having lost their profession. We're now working for insurance companies and hospitals. Instead of turning our energy outward to try to change things, we often turn it inward against each other. Often doctors are jealous of the one who is more creative, disagrees, who has new ideas, who makes more money or who seems to be more popular. As a group, we as doctors are really small-minded people. And the chasm between patient and doctor has been magnified since we've gone full bloom in the information age, so that patients have access to information they didn't have in the past.

Tina: Unfortunately, this occurs at a time when chronic infections are rampant. You've certainly made your case for something you expressed in your speech at the Into the Light Gala, when you said, "The delay in recognizing our nation's Lyme epidemic presents a prime example of our broken health care system. The way in which a society deals with a marginalized population is the signature and indelible stamp of that society's character…give the U.S. health system an F grade for its work here."

Dr. Jemsek: Yes, we do a horrible job of dealing with chronic illness. In a strange way, the Lyme epidemic may be the tipping point for making significant change, because it is so painful and so complex that it's going to force us to finally work it out. It's not going away, no matter how long Gary Wormser holds his breath. We need to think about the whole picture of interaction and interrelationship of chronic infection and epidemiologic control and examine why we have so many other co-morbidities. Could chronic infections be at the root of a lot of our rheumatologic and other diseases?

Tina: Does what you refer to as Lyme Borreliosis Complex or LBC include Lyme and co infections?

Dr. Jemsek: Yes. You see, one thing I noticed with HIV early on, is that we have a different paradigm in that the virus replicates every thirty minutes or so. With LBC we have what we call pleomorphism and polymorphism. Pleomorphism has to do with different life forms and polymorphism has to do with different genomic patterns within the same species. So, as organisms evolve and multiply in a host, they're not carbon copies.

When I talk about the Lyme Complex, what I mean is that I realized early on that our patients are multiply infected. Because I came from an AIDS background, I saw the immune system melt. Although we have a different model with Lyme Borreliosis Complex, the concepts are similar. And what happens is that the immune system melts and we get opportunistic infections that come up after a while. What we saw in the early days of HIV medicine was absolutely bizarre back in the early 80's, because we only read about these things in textbooks. Like,-pneumocystis pneumonia, for example. That was something only kids with leukemia at St. Jude's Hospital in Memphis got after they had received high-dose steroids for months. Or, it was also seen in the malnourished in Auschwitz. But then we started seeing this regularly, and it became by far the most common life-threatening infection in HIV/AIDS.

We also saw the yeast infections and shingles (herpes zoster) come on in twenty year olds. We saw people go blind from cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections. We saw mycobacterium avium complex in blood cultures and as sheets of mycobacterium in stool samples. We saw bizarre stuff, but after a while, it all started to fit into a big pattern. And so, after you see a few hundred patients, you start to realize that when you see a certain CD4 count, the patient's going to get this or that. And we started to get better at that. And we realized how many other systems were affected whether they be metabolic, hormonal, malignancies and so forth.

With Lyme disease, there is absolutely no reason to believe that there are simple answers and simple solutions. When people are really sick, they are multiply infected. And I learned a lot from the animal studies, which indicate that if you're infected with Lyme, you're going to get weak and dizzy. But if you add babesia or bartonella, the animal will die. So I learned that and in my own practice, I started looking for signs to tell me why people relapse or do not get well. And in the early years, I came to the conclusion that they're multiply infected, and you have to treat it as a group or conglomeration of infections and regard it as an immune suppressive illness. In other words, we have a Lyme Borreliosis Complex syndrome and a multisystemic chronic illness.

Tina: In your experience with Lyme patients, have you seen anyone who has exhibited AIDS-type symptoms from immunosuppression?

Dr. Jemsek: Well, I had some AIDS patients who had Lyme. And you know what? The Lyme was worse on the patient.

Tina: Do you currently treat any HIV patients?

Dr. Jemsek: No, I pretty much had to close it down because of the insurance cancellation and lawsuit against me. When that happened, when the dominant insurance company in North Carolina took away our contract, it spelled the end of my HIV practice. When the insurance company sued me, I lost any reasonable chance for a turnaround. What was clearly vicious and premeditated is that they were just trying to take me out; they didn't have to sue me nine months after the news of a medical board review. That was a kill shot, and as I said, they were just trying to take me out.

Basically, their actions assured that a thousand HIV patients were put out on the street. And we had one of the largest HIV practices in the U.S. and the world, and we were going to double our patient population in four years. We did this with a high standard of practice and very good care in a really good setting. It was our dream to do that. As I say on my website, since there were six practitioners seeing new Lyme patients, we probably also had the largest Lyme and tick-borne illness practice in the country. In late 2005, we were seeing eighty to one hundred new patients a month for possible tick-related illness.

Our case is still ongoing and it will probably take another two to three years to resolve. History will judge us for what we've tried to do and I'm fine with that. I don't totally understand it and I don't try to understand it anymore, but there's a reason I've been put in this position. I also have a sense that people are attracted to my story because Americans like underdogs and resiliency. So, I believe that there's a reason I lost my HIV practice, but now I have a new love in medicine and an incredible challenge.

One of the real tragedies about this epidemic is to think about all the sick people who are clueless about their illness and lead wasted lives, or worse, know their illness and can't access care. And then to consider the sheer size of the epidemic is simply staggering. Even with more efficient models of treatment at our clinic, it still takes a couple of years to get people really better. So, anyone can do the math. It's horrible to consider, but this epidemic can bring our nation to it knees.

The Lyme epidemic is going to forever change how we look at chronic illness. We're going to have to get out of the patch-and-pay model that we have and get into real answers. And if we were all really pulling together and trying hard to get answers for complex patients, we would be well on our way to making significant progress. As it is, the politicization of this epidemic and the corporatization of health care have literally put us twenty years behind, and in the end, this indifference to the human condition will have victimized millions.

Tina: Dr. Jemsek, what is your approach to patients and your method for treating Lyme Borreliosis Complex?

Dr. Jemsek: With regard to my approach to patients, I am unable to accept insurance, so there is a financial challenge for patients, which I regret and always appreciate. Almost all patients completely understand this situation, and we do everything we can to help with HICFA forms for insurance filing and so forth. But we all know that health insurers are terrified of the 'black box' which LBC represents, and that their business model is essentially 'anti-patient'.

There is also a travel challenge in most cases, because I see patients from all over the country and quite a few from Europe and other continents. For example, I've had patients come from Russia, Lebanon and Australia to visit the clinic in South Carolina. I've had a dozen to fifteen or more patients come from the Scandinavian countries, as well.

Tina: So despite all the problems forced upon you, patients still come to see you for help.

Dr. Jemsek: Yes, because it's a worldwide epidemic. In fact, we get emails from patients, several per week on average asking, "Can you help me?" People are desperate. It really breaks my heart. I currently only see Borreliosis patients, but I'm seeing sicker patients than I've ever seen before.

Tina: How does the office visit unfold when patients see you for an appointment?

Dr. Jemsek: A new patient intake is a two-hour visit. We ask that the patients complete a clinical medical history form, and they typically bring in an inch or two of records which we review thoroughly. I usually start the patient interview with the question, "Are you doctor referred, or are you here with your doctor's approval or understanding?' Then I ask the patient which doctors they want copied on my consultative note. Some patients say none, some want several doctors copied, and some decide later, so we're happy to do that for them and really encourage the communication.

For as long as I can remember, I have made a practice of providing a copy of the consultative note to each patient, so the patient gets our whole summary with recommendations right away, and of course, I copy any physician who referred the patient or to whom the patient wishes records be sent. Ideally, we want exhaustive but well-organized reviews up front, because if you don't get it on the first or second visit, you likely will never have a history that serves the patient well. In most cases, we set several actions in motion immediately after the visit, and it really isn't until later when laboratory tests and procedures are concluded, that we get a more complete picture. These are extensive documents that I create.

Tina: That's a great help to someone with cognitive dysfunction.

Dr. Jemsek: Exactly. Everyone's from somewhere else, so if someone's on IV therapy, for example, they have to have a collaborating physician at home, no exceptions. And if the patient is going on an oral antimicrobial regimen, we still very much encourage collaboration with a local physician, but we don't demand it.

Patients always have the discretion of taking their records and going to the next physician or finding a physician. I am currently able to interview about five new patients a week on average. That's about all I can do. On the first follow up visit or with a patient that I haven't seen in a year or two, we devote forty-five minutes. On a routine scheduled office appointment, the scheduled time is thirty minutes. So as you can see in that way, from the time allotments, I can only see ten to fourteen patients a day max. If I see more than one new patient a day, it's a really long day.