“It’s All in Your Head:" An Incorrect Assumption Many Doctors Make

February 1, 2014 in Lifestyle by Dr. Robert C. Bransfield, MD

In 1975, I was the only psychiatrist in an eight county area in the rural South. While making hospital rounds, a nurse timidly approached me and handed me a note on a doctor’s prescription pad which read, “This patient has too many complaints, and all the tests are negative. The problems are all in her head and she is hopeless, so I am referring her to you.”

This note was a good example of the confusion that surrounds the mind-body interaction in a state of disease. This same conceptual error persists today, unfortunately among some physicians in highly respected and influential positions. There is considerable confusion regarding terms such as psychosomatic, somatopsychic, hypochondriasis, malingering, and factitious disorder.

Our manner of categorizing these conditions is also confusing. It is incorrect to state that any disease process is even “all in the head” or “all in the body,” since there is constant reciprocal interaction between the brain and the body. The body consists of the brain and the rest of the body, the soma. The brain and soma communicate with each other through four major systems — the voluntary nervous system, the autonomic nervous system, the endocrine system, and the immune system. Any change in the brain can impact the soma and vice versa through communication in these four systems. All diseases have a psychic and somatic component; however, either component may be more dominant in different disease states. It is also incorrect to state that a disease process is either a psychological or a physical process, since all mental processes correlate with physical, biochemical events with the brain.

To discuss the brain/body connection, I’ll begin with a few definitions. Some of these definitions are from the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic Criteria Manual DSM IV:

Psychosomatic: Mental distress results in somatic symptoms.

Somatopsychic: Somatic distress results in mental symptoms.

Hypochondriasis: An excessive fear of having a serious disease based upon misinterpretation of one or more bodily sign or symptom.

Malingering: The intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms motivated by external incentives such as financial compensation, obtaining drugs, avoiding work, etc.

Factitious disorder (Munchausen’s Syndrome): The intentional production of physical or psychological symptoms that are intentionally produced or feigned in order to assume the sick role. The highly controversial factitious disorder by proxy (Munchausen syndrome by proxy) is the intentional production of symptoms in another person.

Somatoforin disorder: A broad diagnostic category of disorders currently used by the American Psychiatric Association in which there is the presence of physical symptoms that suggest a general medical condition which cannot be explained by a medical condition, and is not caused by the direct effect of a substance.

Somatization disorder (previously called hysteria or Briquet’s syndrome): A disorder with multiple symptoms beginning before the age of 30, extending for years, characterized by a combination of pain, gastro-intestinal, sexual and pseudoneurological symptoms which cannot be explained by the presence of a medical condition.

Undifferentiated Somatoform Disorder: Unexplained physical complaints, lasting at least 6 months, but below the threshold for Somatization disorder.

Conversion disorder: Sensory or voluntary motor symptoms resulting from repressed emotional conflicts.

Panic attacks: There is a feeling of alarm and doom accompanied by acute symptoms of a high level of physiological arousal.

Somatic delusion: Somatic complaints as a result of a delusion. There are many unknowns about the true nature of disease at this point in history. Many diseases have not yet been discovered or properly categorized, and the dynamics of common diseases are not fully understood.

Complex, poorly understood diseases are often considered to predominately have a psychological basis until proven otherwise. Tuberculosis, hypertension, and stomach ulcers were once considered to be psychosomatic. A failure to make a diagnosis based upon various so-called “objective tests” is not a basis for a psychiatric diagnosis. The diagnosis of any psychiatric syndrome requires the presence of clearly defined signs and symptoms consistent with each diagnostic category. The presence of a psychiatric diagnosis does not eliminate the possibility of a comorbid somatic diagnosis. It is significant to ask whether all of the signs and symptoms can clearly be explained as a result of a psychiatric syndrome alone. Many patients are given a psychiatric diagnosis as a result of an inadequate medical exam. Also many appropriate psychiatric conditions are often overlooked.

Insurance companies are often quick to support the view that an illness has only a psychiatric basis, since they find it easier to evade responsibility for mental illness. “Compensation neurosis,” “symptom magnification,” and “stress” are favorite terms of consultants paid to give so-called second opinions or paper reviews.

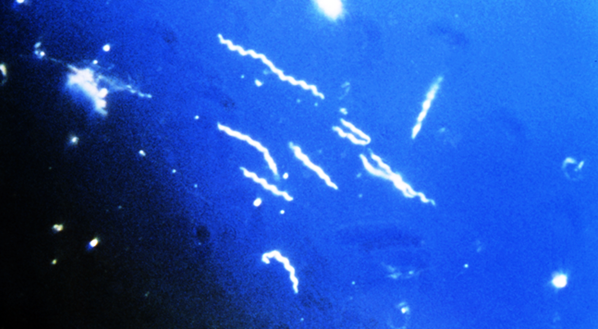

The mind/body interaction is especially complex when understanding late stage Lyme disease. Many patients display central nervous system symptoms from late stage Lyme disease; and the cognitive, psychiatric, and neurological symptoms are often the most disabling symptoms. For this reason, this disease was called neuroborreliosis in other places when it was labeled as Lyme arthritis in Connecticut. In addition, the multitude of somatic symptoms may result in a somatopsychic component, and other comorbid interactive diseases may be present.

Late stage Lyme disease has been erroneously diagnosed as psychosomatic, hypochondriasis, malingering, factitious disorder, Munchausen’s syndrome by proxy, Somatoform disorder, hysteria, and conversion disorder. In a typical case of late stage Lyme disease, a person is reasonably healthy throughout most of their life, and then there is a point in time where a multitude of symptoms progressively appear. The number and complexity of these symptoms may be overwhelming and illness may be labeled hypochondriasis, somatization disorder, or psychosomatic. However, both hypochondriasis and psychosomatic illnesses begin in childhood and are lifelong conditions which vary in intensity depending upon life stressors.

If a complex illness with both mental and physical components begins in adulthood, the likelihood that this is psychosomatic is very remote. To properly understand the mind/body connection, knowledge of general medicine, psychiatry, and the four systems which link the soma and the brain are required. No one has a complete knowledge of all fields of medicine. We must, therefore, retain a sense of compassion and humility, recognize that not all diseases have been discovered or properly understood and be aware that much remains to be learned about the brain/body interaction.

This note was a good example of the confusion that surrounds the mind-body interaction in a state of disease. This same conceptual error persists today, unfortunately among some physicians in highly respected and influential positions. There is considerable confusion regarding terms such as psychosomatic, somatopsychic, hypochondriasis, malingering, and factitious disorder.

Our manner of categorizing these conditions is also confusing. It is incorrect to state that any disease process is even “all in the head” or “all in the body,” since there is constant reciprocal interaction between the brain and the body. The body consists of the brain and the rest of the body, the soma. The brain and soma communicate with each other through four major systems — the voluntary nervous system, the autonomic nervous system, the endocrine system, and the immune system. Any change in the brain can impact the soma and vice versa through communication in these four systems. All diseases have a psychic and somatic component; however, either component may be more dominant in different disease states. It is also incorrect to state that a disease process is either a psychological or a physical process, since all mental processes correlate with physical, biochemical events with the brain.

To discuss the brain/body connection, I’ll begin with a few definitions. Some of these definitions are from the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic Criteria Manual DSM IV:

Psychosomatic: Mental distress results in somatic symptoms.

Somatopsychic: Somatic distress results in mental symptoms.

Hypochondriasis: An excessive fear of having a serious disease based upon misinterpretation of one or more bodily sign or symptom.

Malingering: The intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms motivated by external incentives such as financial compensation, obtaining drugs, avoiding work, etc.

Factitious disorder (Munchausen’s Syndrome): The intentional production of physical or psychological symptoms that are intentionally produced or feigned in order to assume the sick role. The highly controversial factitious disorder by proxy (Munchausen syndrome by proxy) is the intentional production of symptoms in another person.

Somatoforin disorder: A broad diagnostic category of disorders currently used by the American Psychiatric Association in which there is the presence of physical symptoms that suggest a general medical condition which cannot be explained by a medical condition, and is not caused by the direct effect of a substance.

Somatization disorder (previously called hysteria or Briquet’s syndrome): A disorder with multiple symptoms beginning before the age of 30, extending for years, characterized by a combination of pain, gastro-intestinal, sexual and pseudoneurological symptoms which cannot be explained by the presence of a medical condition.

Undifferentiated Somatoform Disorder: Unexplained physical complaints, lasting at least 6 months, but below the threshold for Somatization disorder.

Conversion disorder: Sensory or voluntary motor symptoms resulting from repressed emotional conflicts.

Panic attacks: There is a feeling of alarm and doom accompanied by acute symptoms of a high level of physiological arousal.

Somatic delusion: Somatic complaints as a result of a delusion. There are many unknowns about the true nature of disease at this point in history. Many diseases have not yet been discovered or properly categorized, and the dynamics of common diseases are not fully understood.

Complex, poorly understood diseases are often considered to predominately have a psychological basis until proven otherwise. Tuberculosis, hypertension, and stomach ulcers were once considered to be psychosomatic. A failure to make a diagnosis based upon various so-called “objective tests” is not a basis for a psychiatric diagnosis. The diagnosis of any psychiatric syndrome requires the presence of clearly defined signs and symptoms consistent with each diagnostic category. The presence of a psychiatric diagnosis does not eliminate the possibility of a comorbid somatic diagnosis. It is significant to ask whether all of the signs and symptoms can clearly be explained as a result of a psychiatric syndrome alone. Many patients are given a psychiatric diagnosis as a result of an inadequate medical exam. Also many appropriate psychiatric conditions are often overlooked.

Insurance companies are often quick to support the view that an illness has only a psychiatric basis, since they find it easier to evade responsibility for mental illness. “Compensation neurosis,” “symptom magnification,” and “stress” are favorite terms of consultants paid to give so-called second opinions or paper reviews.

The mind/body interaction is especially complex when understanding late stage Lyme disease. Many patients display central nervous system symptoms from late stage Lyme disease; and the cognitive, psychiatric, and neurological symptoms are often the most disabling symptoms. For this reason, this disease was called neuroborreliosis in other places when it was labeled as Lyme arthritis in Connecticut. In addition, the multitude of somatic symptoms may result in a somatopsychic component, and other comorbid interactive diseases may be present.

Late stage Lyme disease has been erroneously diagnosed as psychosomatic, hypochondriasis, malingering, factitious disorder, Munchausen’s syndrome by proxy, Somatoform disorder, hysteria, and conversion disorder. In a typical case of late stage Lyme disease, a person is reasonably healthy throughout most of their life, and then there is a point in time where a multitude of symptoms progressively appear. The number and complexity of these symptoms may be overwhelming and illness may be labeled hypochondriasis, somatization disorder, or psychosomatic. However, both hypochondriasis and psychosomatic illnesses begin in childhood and are lifelong conditions which vary in intensity depending upon life stressors.

If a complex illness with both mental and physical components begins in adulthood, the likelihood that this is psychosomatic is very remote. To properly understand the mind/body connection, knowledge of general medicine, psychiatry, and the four systems which link the soma and the brain are required. No one has a complete knowledge of all fields of medicine. We must, therefore, retain a sense of compassion and humility, recognize that not all diseases have been discovered or properly understood and be aware that much remains to be learned about the brain/body interaction.

About the author

Dr. Robert Bransfield, MD is a psychiatrist specializing in the link between mental health and microbes. You can learn more by visiting Dr. Robert Bransfield's website mentalhealthandillness.com.

latest posts

tags

Disclaimer: The information on this website is not a substitute for professional medical advice.

Always consult with your treating physician before altering any treatment protocol.

Always consult with your treating physician before altering any treatment protocol.