How Lyme got a bad rap - Lyme, Connecticut, that is

August 1, 2006 in Stories by Dr. J. David Kocurek, PhD

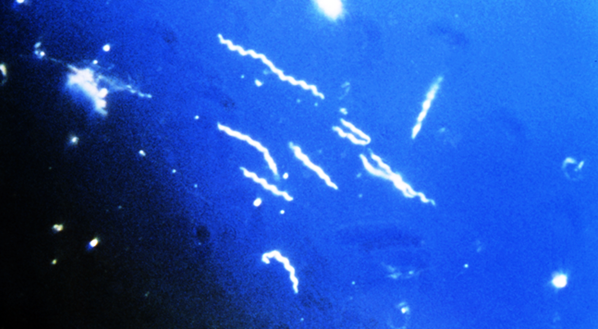

While working on a very comprehensive writing project for my usual advocacy efforts through Stand Up For Lyme, I found the need to research the history of Lyme disease. I think most patients are familiar that the first association between a tick bite and disease was observed in Breslau, Germany. In 1883, Alfred Buchwald described in a journal publication a degenerative skin disorder later named in 1902 as Acrodermatitis Chronica Atrophicans (ACA) by none other than Dr. Karl Herxheimer and a colleague. ACA is associated with a European species of a Borrelia spirochete.

The story usually jumps quickly to the now, too familiar, cluster of outbreaks in eastern Connecticut in the area around the towns of Old Lyme, Lyme and East Haddam. The clusters became noticeable in 1972 and, after delayed investigation, became the first reported appearance of "Lyme" disease in the United States. The name is courtesy of Allen C. Steere, M.D., arheumatology Fellow (specialist-in-training) at Yale who had served previously as a Public Health Service Officer and so had some experience in epidemiology.

Steere was sent by Yale to investigate after the State Health Department gave in to lengthy urging by two local women, Polly Murray and Judith Mensch, who contacted them to point out the unusual number of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) cases in the area. Both women had children with that rare diagnosis, and others in the region supposedly suffered the same fate. Murray recounts in her book, "The Widening Circle: A Lyme Disease Pioneer Tells Her Story", that the family had moved to Lyme in 1959, enjoying an almost idyllic setting. Then strange medical symptoms started first with her, and then with other members of the family until they reached alarming proportions in 1965. She was met with the familiar skepticism by the medical establishment and earned the label of doc-chaser and hypochondriac.

Perseverance, self-education and time for similar stories from the region to come together finally convinced the medical authorities to take some action.

Steere and colleagues arrived on the scene in 1975, at least ten years after children and adults first started presenting with symptoms including erythema migrans (EM) rash, also known as a "bulls eye rash" followed by arthritis. Has anything really changed in the challenges patients are currently facing now that 30 years have passed since Borreliosis was rediscovered and renamed?

Occasionally there is mention of the true first U.S. reported case; that of a physician infected while grouse hunting in Wisconsin (be advised that chicken fried grouse is probably edible, but never order grouse prepared in the English tradition). Fortunately for this individual, an EM rash developed and he presented to a treating physician that was familiar with the European literature and an expert in Borrelia induced skin infection. Dr. Rudolf J. Scrimenti diagnosed the Borrelia infection and was able to arrest the disease during the acute phase with penicillin.

Scrimenti published this case and described both neurologic and arthritic symptoms exhibited by the patient (Arch Dermatol 1970 Jul;102(1):104-5. Erythemachronicum migrans). Scrimenti even corresponded with Steere and visited Yale to inform him of the long European history and strong possibility that the Lyme clusters were likely a form of Borreliosis. However, Steere, the rheumatologist-to-be had been summoned to investigate outbreaks of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. After extensive study and consideration, guess what he concluded? He believedthat he was observing a previously unrecognized form of JRA.

To distinguish his new discovery from the nearly 100 years of documented medical history, Steere added to his conclusion that the causative agent was probably a virus transmitted by an insect or tick vector. This was based on the observation that most cases occurred in the summer and that cases among family members didn't progress in a contagious manner, but rather appeared randomly. One fourth of the interviewed patients recalled a spreading rash on the torso that preceded other symptoms. "Lyme" arthritis and later Lyme disease was launched based on an incorrect diagnosis that would become entrenched in the popular and technical medical literature worldwide. Another case of ignoring established facts because they were NIH - Not Invented Here.

What did happen in all those intervening years? Fortunately, Marie Kroun, M.D., a pediatrician in Denmark, compiled an extensive historic review of pre-Lyme Borreliosis in Europe as part of a presentation prepared fora 2001 conference in the U.K. Kroun's interest developed after seeing the devastating effects of the disease on her young patients. Her volume of literature citations with summaries is astounding. From the 1883 Breslau report through 1975, the year of Steere's misdiagnosed rediscovery of Borreliosis, Kroun meticulously describes 17 references to ACA, 20 to EM, 7 to transmission and 5 discussing the granular (cyst) form of Borrelia, some of this last group dating to 1911. In whole the information collected covers just about all the issues known today, but observed and studied over the past century. Granted, much of the literature is in non-English journals, but enough is in British journals that a thorough investigator would clue in on the references quickly.

A particularly interesting point is raised in modern-day references that describe two examinations of museum specimens. First, in 1884 Austria, Ixodes ticks collected from a fox were preserved. Two of them were more recently found to be infected with B. burgdorferi (Lancet 1995 Nov 18;346(8986): 1367. Antiquity of the Lyme-disease spirochaete in Europe [letter] Matuschka et al).

The second case involves an 1894 museum researcher who collected and preserved white-footed mice found in Dennis, Massachusetts. Modern DNA analysis of ear skin samples from the mice detected B. burgdorferi ospA. This raises the question of B. burgdorferi being brought to North America by European immigration and commerce or likewise taken to Europe via the reverse route.

The motive in recalling this brief history is not only to highlight the unfortunate mistakes made in the rediscovery of Borreliosis in the U.S., but also to demonstrate a far too common pitfall that traps many modern researchers. Those especially who are not properly schooled by their mentors in the process of literature review and its paramount importance to their work, and in the process of investigation are left particularly vulnerable.

When challenged to assess a new situation there are a few fundamental principles that I learned some time ago and came to believe to be universal. I've found them invaluable to guide a number of graduate students and staff assistants in both research and investigative activities.

The first principle is to never jump to conclusions, no matter how obvious the perceived answer may seem. Often times experience builds false confidence in making the easy, but incorrect call. In contrast, a process employing critical analysis to deconstruct a complex of facts into essential elements while still understanding the system interaction can ultimately lead to a far different result and the most plausible, and supportable, explanation. Critical analysis skills are at increasing risk as the educational process in all areas focus more and more on cramming in new information in place of teaching, learning, and processing skills. Information without understanding is of little value.

When Allan Steere reached his conclusions regarding the Connecticut clusters, they came from within his experience base, in spite of competing evidence. Was this result due to limited critical analysis skills, or did it evolve into a defense of ego? Whatever the case, the long struggle of Lyme patients will forever be affected by the delay and misguidance of legitimate science caused by his work and subsequent publication.

And finally, back to the literature search as the foundation of any research investigation, it is perhaps the most dreaded task of the budding student, but also the most important. It may sound cliché to advise starting a journey into an unknown assignment area at the beginning, but by saying 'beginning' I stress the need to find and understand the founding benchmark references related to the endeavor. That's how to avoid replicating work that's already been accomplished, and to make your work contribute by extending the state-of-the-science.

The requirement is to spend a great deal of time examining every relevant source of information, from the beginning to the present. However, the process is not just procedural. For instance, we all have a tendency to believe everything that we read if it's in print. Being in print gives anything written an air of authority and unquestioned acceptance. If the author is an authority figure, the issue is compounded. That's why in reviewing literature one has to maintain a vigil to identify common threads of merit and beware of tangents that are concealed self-promotion.

Steere was handed the answer by Scrimenti and even given the card catalog and the library's address. Had Steere been educated in how to learn and analyze? Did he know how to perform a legitimate literature review? By all appearances, based on the reported history of events, he worked only to substantiate his experience base and his discovery claim of "Lymearthritis" which he thought to be a previously unrecognized clinical entity. He simply started with his answer and left Lyme, Connecticut with a stigma that will be present forever.

The story usually jumps quickly to the now, too familiar, cluster of outbreaks in eastern Connecticut in the area around the towns of Old Lyme, Lyme and East Haddam. The clusters became noticeable in 1972 and, after delayed investigation, became the first reported appearance of "Lyme" disease in the United States. The name is courtesy of Allen C. Steere, M.D., arheumatology Fellow (specialist-in-training) at Yale who had served previously as a Public Health Service Officer and so had some experience in epidemiology.

Steere was sent by Yale to investigate after the State Health Department gave in to lengthy urging by two local women, Polly Murray and Judith Mensch, who contacted them to point out the unusual number of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) cases in the area. Both women had children with that rare diagnosis, and others in the region supposedly suffered the same fate. Murray recounts in her book, "The Widening Circle: A Lyme Disease Pioneer Tells Her Story", that the family had moved to Lyme in 1959, enjoying an almost idyllic setting. Then strange medical symptoms started first with her, and then with other members of the family until they reached alarming proportions in 1965. She was met with the familiar skepticism by the medical establishment and earned the label of doc-chaser and hypochondriac.

Perseverance, self-education and time for similar stories from the region to come together finally convinced the medical authorities to take some action.

Steere and colleagues arrived on the scene in 1975, at least ten years after children and adults first started presenting with symptoms including erythema migrans (EM) rash, also known as a "bulls eye rash" followed by arthritis. Has anything really changed in the challenges patients are currently facing now that 30 years have passed since Borreliosis was rediscovered and renamed?

Occasionally there is mention of the true first U.S. reported case; that of a physician infected while grouse hunting in Wisconsin (be advised that chicken fried grouse is probably edible, but never order grouse prepared in the English tradition). Fortunately for this individual, an EM rash developed and he presented to a treating physician that was familiar with the European literature and an expert in Borrelia induced skin infection. Dr. Rudolf J. Scrimenti diagnosed the Borrelia infection and was able to arrest the disease during the acute phase with penicillin.

Scrimenti published this case and described both neurologic and arthritic symptoms exhibited by the patient (Arch Dermatol 1970 Jul;102(1):104-5. Erythemachronicum migrans). Scrimenti even corresponded with Steere and visited Yale to inform him of the long European history and strong possibility that the Lyme clusters were likely a form of Borreliosis. However, Steere, the rheumatologist-to-be had been summoned to investigate outbreaks of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. After extensive study and consideration, guess what he concluded? He believedthat he was observing a previously unrecognized form of JRA.

To distinguish his new discovery from the nearly 100 years of documented medical history, Steere added to his conclusion that the causative agent was probably a virus transmitted by an insect or tick vector. This was based on the observation that most cases occurred in the summer and that cases among family members didn't progress in a contagious manner, but rather appeared randomly. One fourth of the interviewed patients recalled a spreading rash on the torso that preceded other symptoms. "Lyme" arthritis and later Lyme disease was launched based on an incorrect diagnosis that would become entrenched in the popular and technical medical literature worldwide. Another case of ignoring established facts because they were NIH - Not Invented Here.

What did happen in all those intervening years? Fortunately, Marie Kroun, M.D., a pediatrician in Denmark, compiled an extensive historic review of pre-Lyme Borreliosis in Europe as part of a presentation prepared fora 2001 conference in the U.K. Kroun's interest developed after seeing the devastating effects of the disease on her young patients. Her volume of literature citations with summaries is astounding. From the 1883 Breslau report through 1975, the year of Steere's misdiagnosed rediscovery of Borreliosis, Kroun meticulously describes 17 references to ACA, 20 to EM, 7 to transmission and 5 discussing the granular (cyst) form of Borrelia, some of this last group dating to 1911. In whole the information collected covers just about all the issues known today, but observed and studied over the past century. Granted, much of the literature is in non-English journals, but enough is in British journals that a thorough investigator would clue in on the references quickly.

A particularly interesting point is raised in modern-day references that describe two examinations of museum specimens. First, in 1884 Austria, Ixodes ticks collected from a fox were preserved. Two of them were more recently found to be infected with B. burgdorferi (Lancet 1995 Nov 18;346(8986): 1367. Antiquity of the Lyme-disease spirochaete in Europe [letter] Matuschka et al).

The second case involves an 1894 museum researcher who collected and preserved white-footed mice found in Dennis, Massachusetts. Modern DNA analysis of ear skin samples from the mice detected B. burgdorferi ospA. This raises the question of B. burgdorferi being brought to North America by European immigration and commerce or likewise taken to Europe via the reverse route.

The motive in recalling this brief history is not only to highlight the unfortunate mistakes made in the rediscovery of Borreliosis in the U.S., but also to demonstrate a far too common pitfall that traps many modern researchers. Those especially who are not properly schooled by their mentors in the process of literature review and its paramount importance to their work, and in the process of investigation are left particularly vulnerable.

When challenged to assess a new situation there are a few fundamental principles that I learned some time ago and came to believe to be universal. I've found them invaluable to guide a number of graduate students and staff assistants in both research and investigative activities.

The first principle is to never jump to conclusions, no matter how obvious the perceived answer may seem. Often times experience builds false confidence in making the easy, but incorrect call. In contrast, a process employing critical analysis to deconstruct a complex of facts into essential elements while still understanding the system interaction can ultimately lead to a far different result and the most plausible, and supportable, explanation. Critical analysis skills are at increasing risk as the educational process in all areas focus more and more on cramming in new information in place of teaching, learning, and processing skills. Information without understanding is of little value.

When Allan Steere reached his conclusions regarding the Connecticut clusters, they came from within his experience base, in spite of competing evidence. Was this result due to limited critical analysis skills, or did it evolve into a defense of ego? Whatever the case, the long struggle of Lyme patients will forever be affected by the delay and misguidance of legitimate science caused by his work and subsequent publication.

And finally, back to the literature search as the foundation of any research investigation, it is perhaps the most dreaded task of the budding student, but also the most important. It may sound cliché to advise starting a journey into an unknown assignment area at the beginning, but by saying 'beginning' I stress the need to find and understand the founding benchmark references related to the endeavor. That's how to avoid replicating work that's already been accomplished, and to make your work contribute by extending the state-of-the-science.

The requirement is to spend a great deal of time examining every relevant source of information, from the beginning to the present. However, the process is not just procedural. For instance, we all have a tendency to believe everything that we read if it's in print. Being in print gives anything written an air of authority and unquestioned acceptance. If the author is an authority figure, the issue is compounded. That's why in reviewing literature one has to maintain a vigil to identify common threads of merit and beware of tangents that are concealed self-promotion.

Steere was handed the answer by Scrimenti and even given the card catalog and the library's address. Had Steere been educated in how to learn and analyze? Did he know how to perform a legitimate literature review? By all appearances, based on the reported history of events, he worked only to substantiate his experience base and his discovery claim of "Lymearthritis" which he thought to be a previously unrecognized clinical entity. He simply started with his answer and left Lyme, Connecticut with a stigma that will be present forever.

latest posts

tags

Disclaimer: The information on this website is not a substitute for professional medical advice.

Always consult with your treating physician before altering any treatment protocol.

Always consult with your treating physician before altering any treatment protocol.