Transcendence in Chronic Illness: Why “Giving In” is Not “Giving Up"

July 1, 2014 in Lifestyle by Ginger Savely, RN, FNP-C

In the book "Learning to Fall: The Blessings of an Imperfect Life", Philip Simmons, suffering from Lou Gehrig’s disease, finds that his disability forces him to embrace life more fully. He finds transcendence in stillness, in doing nothing, in letting go of the expectations he had of life prior to his illness. He writes “When we learn to fall, we learn that only by letting go our grip on all that we ordinarily find most precious -our achievements, our plans, our loved ones, our very selves- can we find, ultimately, the most profound freedom. In the act of letting go of our lives, we return more fully to them.”

My experience with chronic illness has been that patients go through the traditional stages of grieving that follow all sorts of loss: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and finally acceptance. The first three stages can last a long time with patients trying to ignore or fight their symptoms, resentful of their limitations and angry with themselves for the inability to carry on in spite of them. Then the depression and despair hits and it becomes difficult to motivate one’s self to do what is necessary to begin to heal.

It is when patients arrive at the stage of acceptance of the reality of their situation that healing of the body and the mind begins. This is the time I refer to as “giving in”. It is often signaled by an ability on the part of the patient to see the humor in his shortcomings and a willingness to stop working against the illness and start working with it. A difficult lesson for chronically ill patients to learn is that “giving in” is not “giving up”. The reward for letting go and submitting oneself to the full experience of one’s new reality is a kind of transcendence that the non-stop, on-the-go healthy person can never fully experience.

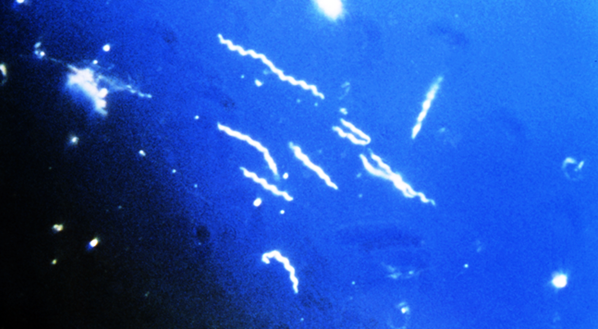

Some may argue that the only way to overcome hardship is to fight back with all you’ve got. This philosophical approach may be appropriate in the case of some types of adversity, but not in the case of chronic disease where the immune system is under attack by pathogens or auto-immunity. My observation, based on the treatment of a thousand chronic Lyme patients, is that when patients stop struggling with their predicament, the healing begins.

Everyone has a spiritual side - some are just more in touch with theirs than others. I am not necessarily talking about belonging to an organized religion, although some may choose this path to their spiritual selves. Spirituality is that which lies beyond the ordinary range of perception. It takes us above and beyond the material world, outside of the physical body yet deeper into the soul. It can be touched by listening to beautiful music, watching a sunset or holding a newborn baby.

Whenever you forget yourself and forget time and are wrapped up in the ecstasy of the moment, you are nourishing your spiritual self. This kind of transcendence over daily existence gives meaning to our lives and relieves us, if only temporarily, from our worries and our pain. Unlike many eastern traditions, the western world has not been as aware of the importance that nourishing the soul has for physical and mental health.

Chronic illness is a challenge that cries out for transcendence, a time when the spiritual self is called upon more than ever, both for coping and for finding meaning in a seemingly cruel and unfair fate. The emptiness felt by those who face a life devoid of many of the joys that nourished it before, stimulates the search for new motivation to carry on and sustain hope. Many people with chronic illnesses find that the blessing in their situation is that they have the time and the need to “stop and smell the roses”, discovering that their lives, and often their disease course, are benefited enormously.

For some, the word transcendence conveys an image of religious mystics living blissfully on a mountaintop, having mastered the art of living in another dimension, unattached to and unaware of the physical world. For most of us, this type of lifestyle is not only implausible but also unappealing, as there are joys to be found in the material plane as well! For purposes of discussion, let us think of transcendence as a natural “high” – a temporary sense of joy achieved by being totally present in the moment, without worry of the past or care of the future.

Most of the time we live very grounded to our physical needs, aware of hunger, thirst, pain, heat, cold, and discomfort of all kinds. During transcendence there is no physical or emotional pain, because for that brief time one’s actual body is out of the focal plane: possibilities are limitless as we enter the playground of the mind.

Achieving transcendence is a personal matter and each of us have different motivators that facilitate this for us – different “distractions” if you will, that allow us to become lost in the moment and elevated to a higher plane. You may or may not know what these are for you, but chances are that while chronically ill, you will need to modify your usual approach due to the limitations of your disease. Skydiving or reading Shakespeare, for example, may be currently out of the question. Meditation, yoga, listening to beautiful music or aromatherapy may be more in line with your diminished capabilities.

For those who are ill and lost in despair and at some point in their lives found solace in a particular religion or church, re-establishing connection may be an answer. For many, organized religion with its comforting rituals and sense of community is one of the best paths to transcendence. For others, the experience needs to be more unstructured, unorthodox and personal.

Spiritual experiences are ubiquitous, if one takes the time to stop and pay attention. I feel blessed to have found spirituality in my profession, as have many others in the serving fields. In fact, the definitive path to transcendence is that of serving others: giving unqualified, unconditional love, helping others by giving joy, comfort and support. Even for the chronically ill there are opportunities to serve. You may not have the stamina to participate in Habitat for Humanity or Meals on Wheels, but there is always someone less fortunate than yourself who can benefit from your reassuring words and calming advice. You will find that the gift you receive is far greater than the gift you give.

Some with chronic disease are lucky enough to have times of remission during which time they are able to engage in physical activities that facilitate a spiritual high. Steven Kotler, a Los Angeles-based journalist in his mid-30s found transcendence in the sport of surfing during his better days while sick with Lyme disease. He tells his story in the book, "West of Jesus: Surfing, Science and the Origin of Belief" (Bloomsbury, June 2006).

When I was ill for several years, gentle swimming was my meditation. My daughter, while recovering from a long illness, spoke of “becoming one” with the sea turtles when she swam with them in Hawaii. Others have said the same of swimming with dolphins. In fact, relating to animals is the key for many of us and even the elderly and disabled can enjoy this type of communion with pets of all kinds at the bedside.

The key to dealing with chronic illness is finding a way to lose the SELF. The chronically ill become, understandably, self-obsessed, focusing on every detail as their body betrays them. This self-absorption becomes misinterpreted, to the disadvantage of the patient, by health care providers who are unable to look beyond the patient’s behavior to the precipitating cause.

Looking for ways to achieve transcendence is the key, not only for finding grace in a disheartening situation but for letting go and allowing natural restorative energies to flow. Giving in to what is happening to your body, having faith that the best outcome will prevail, is a peaceful way to facilitate healing. Never confuse this with ”giving up” because as long as there is the joy of transcendence, there is healing, and hope for better days to come.

My experience with chronic illness has been that patients go through the traditional stages of grieving that follow all sorts of loss: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and finally acceptance. The first three stages can last a long time with patients trying to ignore or fight their symptoms, resentful of their limitations and angry with themselves for the inability to carry on in spite of them. Then the depression and despair hits and it becomes difficult to motivate one’s self to do what is necessary to begin to heal.

It is when patients arrive at the stage of acceptance of the reality of their situation that healing of the body and the mind begins. This is the time I refer to as “giving in”. It is often signaled by an ability on the part of the patient to see the humor in his shortcomings and a willingness to stop working against the illness and start working with it. A difficult lesson for chronically ill patients to learn is that “giving in” is not “giving up”. The reward for letting go and submitting oneself to the full experience of one’s new reality is a kind of transcendence that the non-stop, on-the-go healthy person can never fully experience.

Some may argue that the only way to overcome hardship is to fight back with all you’ve got. This philosophical approach may be appropriate in the case of some types of adversity, but not in the case of chronic disease where the immune system is under attack by pathogens or auto-immunity. My observation, based on the treatment of a thousand chronic Lyme patients, is that when patients stop struggling with their predicament, the healing begins.

Everyone has a spiritual side - some are just more in touch with theirs than others. I am not necessarily talking about belonging to an organized religion, although some may choose this path to their spiritual selves. Spirituality is that which lies beyond the ordinary range of perception. It takes us above and beyond the material world, outside of the physical body yet deeper into the soul. It can be touched by listening to beautiful music, watching a sunset or holding a newborn baby.

Whenever you forget yourself and forget time and are wrapped up in the ecstasy of the moment, you are nourishing your spiritual self. This kind of transcendence over daily existence gives meaning to our lives and relieves us, if only temporarily, from our worries and our pain. Unlike many eastern traditions, the western world has not been as aware of the importance that nourishing the soul has for physical and mental health.

Chronic illness is a challenge that cries out for transcendence, a time when the spiritual self is called upon more than ever, both for coping and for finding meaning in a seemingly cruel and unfair fate. The emptiness felt by those who face a life devoid of many of the joys that nourished it before, stimulates the search for new motivation to carry on and sustain hope. Many people with chronic illnesses find that the blessing in their situation is that they have the time and the need to “stop and smell the roses”, discovering that their lives, and often their disease course, are benefited enormously.

For some, the word transcendence conveys an image of religious mystics living blissfully on a mountaintop, having mastered the art of living in another dimension, unattached to and unaware of the physical world. For most of us, this type of lifestyle is not only implausible but also unappealing, as there are joys to be found in the material plane as well! For purposes of discussion, let us think of transcendence as a natural “high” – a temporary sense of joy achieved by being totally present in the moment, without worry of the past or care of the future.

Most of the time we live very grounded to our physical needs, aware of hunger, thirst, pain, heat, cold, and discomfort of all kinds. During transcendence there is no physical or emotional pain, because for that brief time one’s actual body is out of the focal plane: possibilities are limitless as we enter the playground of the mind.

Achieving transcendence is a personal matter and each of us have different motivators that facilitate this for us – different “distractions” if you will, that allow us to become lost in the moment and elevated to a higher plane. You may or may not know what these are for you, but chances are that while chronically ill, you will need to modify your usual approach due to the limitations of your disease. Skydiving or reading Shakespeare, for example, may be currently out of the question. Meditation, yoga, listening to beautiful music or aromatherapy may be more in line with your diminished capabilities.

For those who are ill and lost in despair and at some point in their lives found solace in a particular religion or church, re-establishing connection may be an answer. For many, organized religion with its comforting rituals and sense of community is one of the best paths to transcendence. For others, the experience needs to be more unstructured, unorthodox and personal.

Spiritual experiences are ubiquitous, if one takes the time to stop and pay attention. I feel blessed to have found spirituality in my profession, as have many others in the serving fields. In fact, the definitive path to transcendence is that of serving others: giving unqualified, unconditional love, helping others by giving joy, comfort and support. Even for the chronically ill there are opportunities to serve. You may not have the stamina to participate in Habitat for Humanity or Meals on Wheels, but there is always someone less fortunate than yourself who can benefit from your reassuring words and calming advice. You will find that the gift you receive is far greater than the gift you give.

Some with chronic disease are lucky enough to have times of remission during which time they are able to engage in physical activities that facilitate a spiritual high. Steven Kotler, a Los Angeles-based journalist in his mid-30s found transcendence in the sport of surfing during his better days while sick with Lyme disease. He tells his story in the book, "West of Jesus: Surfing, Science and the Origin of Belief" (Bloomsbury, June 2006).

When I was ill for several years, gentle swimming was my meditation. My daughter, while recovering from a long illness, spoke of “becoming one” with the sea turtles when she swam with them in Hawaii. Others have said the same of swimming with dolphins. In fact, relating to animals is the key for many of us and even the elderly and disabled can enjoy this type of communion with pets of all kinds at the bedside.

The key to dealing with chronic illness is finding a way to lose the SELF. The chronically ill become, understandably, self-obsessed, focusing on every detail as their body betrays them. This self-absorption becomes misinterpreted, to the disadvantage of the patient, by health care providers who are unable to look beyond the patient’s behavior to the precipitating cause.

Looking for ways to achieve transcendence is the key, not only for finding grace in a disheartening situation but for letting go and allowing natural restorative energies to flow. Giving in to what is happening to your body, having faith that the best outcome will prevail, is a peaceful way to facilitate healing. Never confuse this with ”giving up” because as long as there is the joy of transcendence, there is healing, and hope for better days to come.

latest posts

tags

Disclaimer: The information on this website is not a substitute for professional medical advice.

Always consult with your treating physician before altering any treatment protocol.

Always consult with your treating physician before altering any treatment protocol.